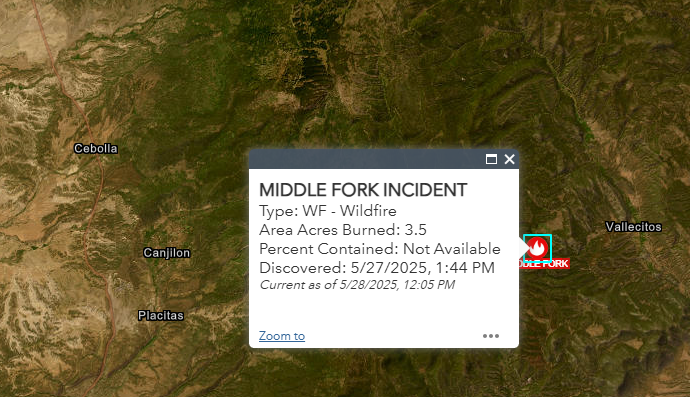

New Mexico’s forests are facing growing challenges from insects and disease, and the impacts are becoming increasingly visible across the landscape.

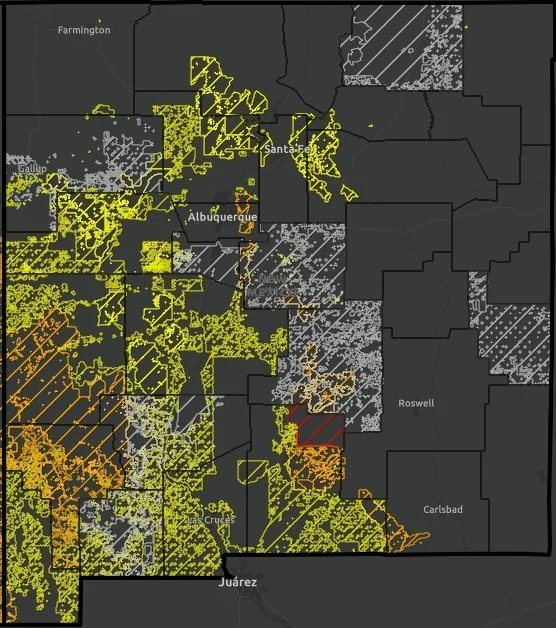

In recent years, hotter and drier conditions have created the perfect environment for widespread outbreaks, leaving many residents concerned about the health of the trees that surround their communities. According to New Mexico’s 2024 Forest Health Summary, “The total number of forest and woodlands mapped in 2024 with damage from insects, disease and abiotic conditions was 406,000 acres on all landownership types in New Mexico, an increase of 42,000 acres or 12% since 2023.”

This year, northern New Mexico residents have noticed large patches of trees turning brown, raising alarm about what’s happening in the forests. Much of this damage is linked to the insect activity.

The relationship between insects, drought, and wildfire is an ongoing cycle. Hotter temperatures and reduced precipitation weaken trees, making them more susceptible to insect attack. In turn, beetle-killed or disease-weakened trees create more dead and susceptible fuel for future wildfires. By looking closer at how insects and fire interact, we can better prepare for the challenges ahead and explore strategies to make our forests more resilient.

Below you will find information about:

A Primer on Tussock Fir Outbreaks

Stay safe and be well,

Megan

A Primer on Tussock Fir Outbreaks

Summary of today’s primer:

History - High-elevation forests across New Mexico have experienced a tussock moth outbreak over the past three years which has left many trees, primarily Douglas fir and White fir, with damaged orange crowns and has caused some mortality.

Takeaways - The Douglas-fir tussock moth is just one of many insects and diseases impacting forest health across the state. Although the current tussock moth epidemic is waning in many places, forests across New Mexico continue to face growing pressures from bark beetles, defoliating moths, engraver beetles, and other pests and pathogens. These disturbances weaken individual trees and can trigger large-scale mortality events. As the climate becomes hotter and drier, and forests experience greater water and resource stress, pest and disease activity is intensifying. The resulting tree death reshapes landscapes in different ways depending on forest type.

Next steps - Targeted, ecologically sound thinning remains one of the most effective tools for strengthening forest resilience, both against insects and disease, and against wildfire.

………………………………

The basics of defoliation

The following is based on a presentation from Victor Lucero. For more information, visit the Forest Health website or contact Victor.

Why do all those trees look dead?

An outbreak of a native insect called the Douglas-fir tussock moth (DFTM) has defoliated trees – meaning, damaged the leaves of trees – in and around the Santa Fe National Forest. The three-year outbreak has likely just ended, according to Victor Lucero, Forest Health Program Manager for the New Mexico Forestry Division. In late August 2025, the Greater Santa Fe Fireshed Coalition Ambassadors invited Lucero to talk about the insect, what caused its outbreak, and how the outbreak has impacted forest health.

What is the Douglas-fir tussock moth?

The Douglas-fir tussock moth is endemic to western North America: It belongs here, it will always be here, and it’s always present in the forest.

The Douglas-fir tussock moth overwinters in an egg mass that contains a few hundred eggs. In the spring, those eggs hatch into the first instar caterpillars (the first stage of development), which disperse by “ballooning” – so wherever the egg masses are, the insect will disburse through wind currents or thermals. The emergence of this first instar coincides with bud burst (the emergence of new growth on trees). Near Santa Fe, that has been around the middle of May for the last couple of years. The insect then begins to develop into larger caterpillars and finally reach a stage of caterpillar that resembles the photo below. Tussock moths generally pupate in late summer, forming cocoons from which they emerge as moths.

This insect is a strict defoliator, meaning that it feeds on the needles of trees; it does not feed on buds, it does not burrow into trees, it does not kill trees by girdling the tree stems. As the name suggests, Douglas fir is one of the hosts, but the tussock moth can also attack other trees such as spruce and true firs.

Douglas-fir tussock moths are defoliators. Does that mean they’re killing trees?

The affected trees, especially visible with their reddish-brown needles, are in different stages of defoliation. Many of them will die, and many of them will not.

Seeing the discolored tree canopies leads a lot of folks to wonder why the trees are dying. This has led to a lot of commentary, a lot of concern, and rightfully so; nobody wants to see the forest going from green to this. However, these needles are just responding to either one single bite or multiple bites from caterpillars.

So what is actually happening to the trees, post-defoliation? When we look closely, the buds of many impacted trees are, even now, starting to open. Defoliation stresses trees, but won’t necessarily kill them unless they are hit multiple years in a row. Victor Lucero has observed trees that are 80% defoliated, and the following year they break bud and are fine, given no other defoliation event by Douglas-fir tussock moth or another insect. That said, there will be some mortality. Driving through the forest, you’ll see some gray, dead trees; those will not come back, and those can be potential wildfire hazards.

What is the cause and extent?

What caused this outbreak in New Mexico?

It's important to note that whenever there's an outbreak of an insect, it usually is triggered by something else. In this case, there is a problem with too many trees per unit area (the forests are too dense) in many woodlands and forests. The reality is that this insect is responding to an abundance of food.

The Douglas-fir tussock moth has a high rate of mortality early after hatching because of either starvation or predation, but more so when needles aren't readily available. Our dense forests provide a veritable buffet table for the moths and provide a safe place for them to mate and lay their eggs, continuing the cycle. It’s common for Victor to count 50 trees in a 20-foot by 20-foot area, and that's just not sustainable for the viability of the tree or for the health of the entire forest.

The Douglas-fir tussock moth has been attacking white fir because it is extremely overstocked in our high-elevation and northern forests. Fire, which we have long been unnaturally suppressing, belongs in our forests because it reduces the amount of fuel (flammable material) on the forest floor and keeps certain species of trees at levels that were historically documented. For white fir, historically, there were notably fewer trees per acre and were less widespread than they are now. The high density of a tree like white fir is supporting a very large population of the tussock moth which in turn is reaching the point of an outbreak wherever we see high densities of white fir.

How do we know how bad the outbreak is?

One way we monitor and track tussock moth activity is through pheromone traps. The traps have a lure and are coated with sticky glue impregnated with a sex pheromone to attract male moths (the females do not have wings and are not mobile). This acts as an early detection system – if we catch 25 male moths on average at a five-trap site, that triggers us to then go and subsequently count for egg masses.

Last year, in an area of Hyde Park (near Santa Fe Ski Basin), there were 300-400 egg masses in 29 trees. That’s a breaking point. Victor recently monitored six different sites in northern NM, from Black Canyon to the Aspen Ranch, and didn't find a single egg mass.

Is the outbreak over?

There are naturally occurring predators and parasitoids, mostly wasps and fly species, that affect tussock fir populations and keep them in check, but more importantly there is something called a nuclear polyhedrosis virus, NPV. It occurs naturally in the environment, and when caterpillars of the Douglas-fir tussock moth come in contact with that virus, they begin to wilt, like a dangling ornament on a tree.

When a caterpillar gets infected with this virus, the virus quickly reproduces and then causes the caterpillar to rupture. When this happens, it releases millions of viral particles per caterpillar which then spreads to and infects other caterpillars. Around the third year of a tussock moth outbreak, the viral load becomes widespread enough that the population collapses.

Typically, an outbreak lasts three, maybe four years. In northern NM, we're at the end of the third year and we’re seeing that population collapse happening.

Why are there signs instructing people “DO NOT TOUCH” the Douglas-fir tussock moth?

There have been multiple incidents over the last couple of years of people experiencing tussockosis. This is an affliction where tufts of very small, compressed hairs on the Douglas-fir tussock moth come into contact with someone’s skin and cause irritation, especially among people who are predisposed to allergic reactions.

What’s next, and what can be done?

What should we expect to happen next?

Victor and state Forestry Division will continue to monitor tussock moth activity. Based on rudimentary sampling, it looks like the Douglas-fir tussock moth population has collapsed and now it’s a matter of determining how much tree mortality has occurred. Land managers will then have to decide what to do about the standing dead trees. Monitoring will also continue because there is a potential for bark beetles, like fir engraver beetles, to come in and attack these weakened defoliated trees. Knowing how much insect activity is happening in these defoliation sites allows Forestry Division to give a better assessment as to the overall health of the trees.

Bark beetles attack stressed trees – and they’re outright tree killers. Male bark beetles colonize the trees, emit a sex pheromone to draw in females, and eggs hatch into grubs which feed on the phloem - the phloem is what transports water and nutrients between the roots and leaves. The beetles also introduce a staining fungus, blue-stain fungus.

All of this is happening underneath the bark where we don’t see the damage. Often, the first sign of a beetle outbreak is the tree canopy turning an orange color, called fading. The feeding action that girdles the stem and the introduction of the staining fungus very quickly leads to mortality.

Bark beetles have been here, they’ll continue to be here, and they will typically target stressed trees because they’re easier to colonize: If trees are doing well, there's a sustained sap flow, and the system is under pressure so a bark beetle trying to attack it will literally be pitched (pushed) out because of the resiliency of the host.

However, if there's a beetle outbreak that is triggered by a big tussock moth defoliation event, the numbers of bark beetles can increase dramatically, disperse widely, and overcome even healthy trees. That’s where things can become very problematic, where you have outbreaks of bark beetles that continue for several years. For now, Victor hasn’t seen a whole lot of bark beetles in the areas near Santa Fe that have been hit by defoliation.

What can be done to help the forest?

Wherever we see thinning treatments, those trees have less competition, but where we have high densities of trees, there’s a lot of competition going on. Where densities of trees remain unnaturally high, the data collected on the Douglas-fir tussock moth over multiple decades shows that every ~7 to 10 years, we can expect to see another outbreak of Douglas-fir tussock moth like this, which will last 3-4 years. These insects are capitalizing on the abundance of food: where the trees are canopy-to-canopy and there are lots of them, it’s easy for these animals to disperse from one tree to the next. The best thing we can do is continue to thin the forest in a targeted and ecologically-sound way to improve its resilience to pests, something which also improves its resilience to wildfire.

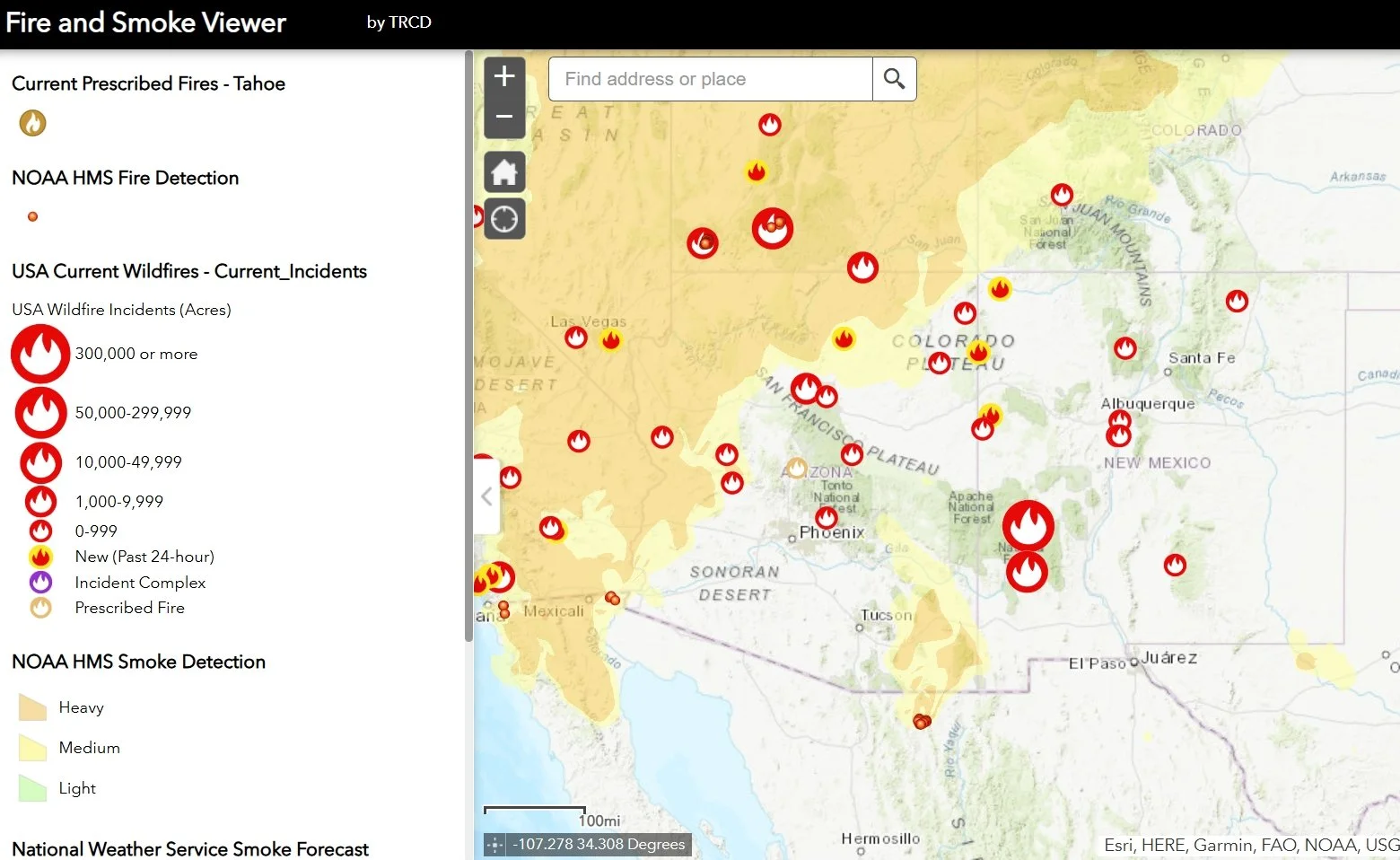

Pests and Fire

How defoliation and insect-driven mortality impacts wildfire susceptibility

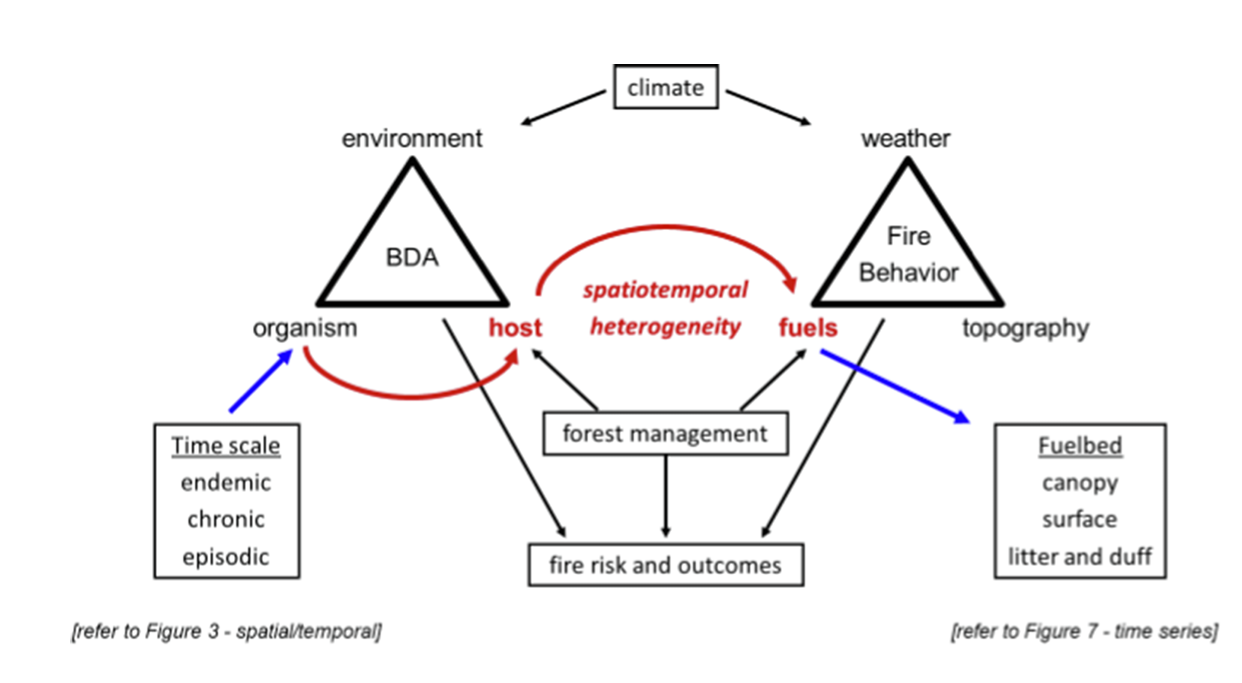

A western USA coniferous forest landscape where BDAs are a common and natural feature. BDAs interact with abiotic factors such as fire and drought to determine forest composition and structure at stand and landscape scales.

A common belief is that forests infested by insects, pathogens, and parasitic plants, also known as biological disturbance agents, or BDAs, are “unhealthy” and are, therefore, at greater risk of fire. However, more recent research indicates that BDAs often have a more nuanced, context-dependent influence on fire. Collaborative research, funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Forest Service and Oregon State University, is described in the article, “The complexity of biological disturbance agents, fuels heterogeneity, and fire in coniferous forests of the western United States.” This manuscript provides a conceptual framework for how to relate BDAs, fuels and fire based on a review of supporting literature.

Main takeaways from the review:

BDAs include diverse biota, including native and non-native pathogens, insects, and parasitic plants, which both respond to and reshape forest composition and structure by causing tree decline and mortality and changing species composition.

BDAs impacts on fuels, and thus on fire likelihood, behavior, and severity, depend on the timing, scale, and extent of outbreaks, as well as preexisting stand conditions.

Most BDA groups have received little attention from fire researchers, despite many being pervasive across the western United States. The role of BDAs in shaping fuel characteristics and fire risk is very relevant under today’s warming and drying climate.

The way BDAs interact with fire depends primarily on how significantly BDAs influence canopy, surface, and litter/duff fuels.

BDAs influence fuel structure in live crowns by killing leaves, branches, and whole trees, they cause species-specific tree mortality, and affect competitive interactions among tree species, all of which modify canopy, surface, and litter and duff fuels, which also vary with time.

Dead canopy biomass eventually moves to the forest floor and understory, increasing surface and ground fuels, decreasing canopy fuels and affecting microclimate at the scale of the mortality or defoliation. The influence of BDAs on horizontal and vertical patterns of fuels is complicated by the magnitude of mortality, as well as the structure and composition of the stand before and subsequent to BDA events. In general, surface fuels increase, and canopy fuels decrease, while litter and duff may increase associated with the conversion of aboveground live biomass to dead biomass.

The role of BDAs in increasing active crown fire is when the temporal aspect of the outbreak is at its peak of intensive tree mortality and there are many trees with dead (green foliage can be dead and dry) and red foliage. Fires in systems in the red phase can have higher fire intensity, faster rate of spread, lower crowning thresholds, greater consumption of fine dead branches, and more crown fire than predicted by fire behavior models. However, the potential for active crown fire decreases after snags fall due to lower canopy connectivity and canopy bulk density, as well as conversion to surface fuels that do not play a large role in fire spread.

Although BDAs may increase fire severity in some stands during some time periods, heterogeneity in fuels created by BDAs can increase diversity in fire severity by reducing homogeneity in forest conditions and fuels that support larger patches of high-severity fire.

A conceptual framework of the influence of BDAs on fuels and fire behavior and the relationships among associated factors. Together, with forest management and weather, BDAs influence the spatial heterogeneity of fuels and associated fire risk and outcomes.

Although BDAs may elevate fire risk in some stands or time periods, their influence is variable. A useful way to understand their role is to distinguish between outbreaks that cause rapid tree mortality and chronic agents that slowly drive decline. This framing highlights how BDAs shift live fuels to dead fuels, alter moisture and chemistry, and redistribute fuels across canopy, surface, and ground layers over short- and long-term timescales. Ultimately, the effects of BDAs on fire cannot be generalized. They depend on the type of BDA, the structure and composition of the forest, and the spatial and temporal patterns of disturbance.