Happy Wednesday!

Effective communication is one of the most critical elements of wildfire preparedness. Whether you're a resident, a community leader, or part of an emergency response team, the ability to share and access accurate and timely information can help save lives and minimize damage. Today, digital platforms play a vital role in how we prepare for and respond to wildfires. Social media has emerged as a powerful way to quickly reach large audiences, provide real-time updates, and engage communities before, during, and after fire events. Similarly, interactive maps offer a user-friendly visual way to track wildfire activity, air quality, and evacuation zones, helping people stay informed as conditions evolve. Today's newsletter highlights trusted resources and best practices for communicating during wildfire events, along with a curated list of essential apps and websites that provide up-to-the-minute wildfire information, air quality monitoring, and fire restrictions tailored specifically for New Mexico. Whether you're preparing in advance or responding in the moment, these tools will help you stay informed and ready to act.

This Wildfire Wednesday, I’m proud to also introduce a new element: the Fire Adapted New Mexico Member and Leader Spotlight, beginning with one of the Network’s dedicated leaders. Each month, this newsletter will highlight an active FACNM Member or Leader, showcasing their efforts to build fire-adapted communities, the insights and advice they’ve gained along the way, and their vision for learning to live more safely with fire.

This Wildfire Wednesday features:

Wildfire communication resources and best practices

-Megan

Wildfire Communication Resources & Best Practices

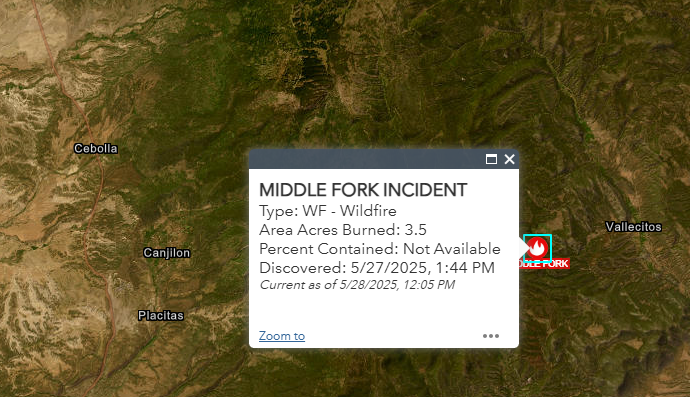

New Mexico Fire Viewer

NMFWRI’s GIS Team has developed the New Mexico Fire Viewer, an interactive web map that provides access to real-time and historical wildfire data. The web map integrates satellite imagery and GIS layers, allowing users to search for active wildfires by name and view perimeter boundaries and hot spots. These updates, sourced from satellite infrared images, refresh every few hours. Originally launched to track the Hermit’s Peak and Calf Canyon Fires near Las Vegas, NM, the Fire Viewer now includes wildfire data statewide, covering current, recent, and historical fires. View the NM Fire Viewer at https://nmfireviewer.org/.

The Fire Viewer includes multiple GIS layers to enhance situational awareness:

Smoke forecasts

Land ownership data

Soil burn severity maps

Burn scars from past fires

Building footprints (houses, barns, and other structures, sourced from Microsoft)

Vegetation treatment data from NMFWRI

………………………………………………………………………………

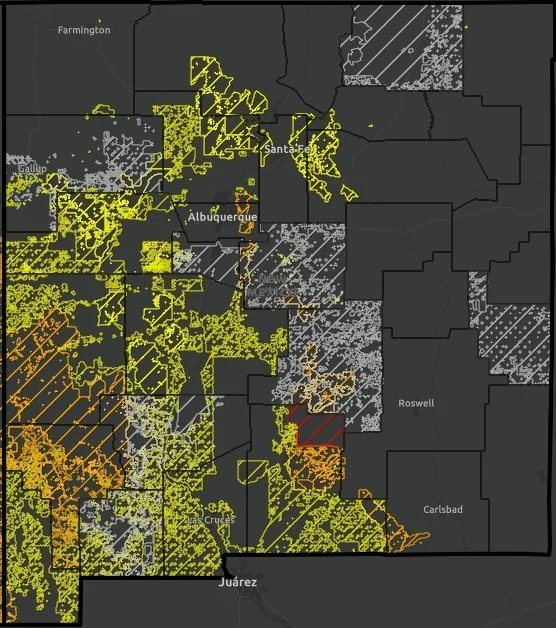

NM Fire Info Southwest Area Fire Restrictions Map

NMFireInfo.com is an interagency effort in New Mexico, created to provide timely and accurate information about wildfires and fire restrictions across the state.

One of the key features of the site is an interactive map that helps residents, landowners, and visitors quickly identify current fire restrictions in effect throughout the Southwest region. By clicking on a specific area of interest, you can access direct links to the latest fire restriction orders, closures, and/or official news releases for that location. While the map is a valuable resource, it may not always capture the most recent updates for every jurisdiction. For the most accurate and up-to-date fire restriction information, it’s always a good idea to check with your local fire department, government agency, or (if you're traveling to visit public lands) the relevant local land management office.

………………………………………………………………………………

AirNow Fire and Smoke Map

The AirNow Fire and Smoke Map is a tool for monitoring fine particle pollution (PM2.5) from wildfires. It does not track all airborne toxins or pollutants. This tool focuses on PM2.5, tiny particles in smoke that can travel deep into the lungs, enter the bloodstream, and pose serious immediate and long-term health risks - even to people far from a fire’s origin. Exposure to PM2.5 is especially dangerous for individuals with asthma, heart or lung conditions, children, older adults, and those who work outdoors. The map uses the Air Quality Index (AQI), a simple, color-coded scale ranging from "Good" to "Hazardous", to help users quickly assess how safe the air is to breathe.

Available in both English and Spanish, the interactive map allows you to click on icons to view detailed, location-specific information. This includes the current AQI, historical air quality trends, and the presence of any nearby fires or visible smoke plumes. For each AQI category, the map also highlights the groups most at risk and offers practical recommendations to reduce smoke exposure, such as staying indoors, using air purifiers, or wearing N95 masks. Understanding AQI empowers communities to make safer, healthier choices during wildfire events.

………………………………………………………………………………

Watch Duty

Watch Duty is a free app available for both iPhone and Android that provides real-time alerts about nearby wildfires, prescribed fire activities, and suppression efforts. The app offers detailed information, including active and historical fire perimeters, red flag warnings, satellite hotspots, and more. Unlike crowdsourced platforms, Watch Duty is powered by a trusted network of active and retired firefighters, dispatchers, and first responders. These experts monitor radio scanners and collaborate 24/7 to deliver up-to-the-minute updates.

If a wildfire threatens life or property, Watch Duty sends immediate alerts directly to your device. Each incident is continuously monitored, and updated alerts are sent until the threat is removed or the fire is fully contained.

………………………………………………………………………………

Living With Fire Social Media Toolkit

The Living With Fire Social Media Toolkit is a ready-to-use resource designed to help users share important wildfire preparedness information across your social media platforms. It includes a range of prepared messages that you can post as-is or customize to fit your audience’s needs. Topics include evacuation planning, creating defensible space, home hardening, living with smoke, prescribed fire, post-fire recovery, and preparing for post-fire flooding. The toolkit also features downloadable graphics to complement each key message. All materials, including graphics and messages, are available in both English and Spanish to help you reach diverse communities effectively.

An example of one of their pre-drafted messages:

“Strong winds can move wildfire smoke from an area on fire to communities otherwise unaffected, greatly reducing air quality and extending the health risks of wildfire. Learn more about smoke and how it travels at www.iqair.com”

………………………………………………………………………………

NWCG Community Engagement Recommendations

In February of this year, the updated NWCG Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) Mitigation Field Guide was released, offering practical guidance for mitigation practitioners of all experience levels. The guide provides strategies and recommendations for effectively and efficiently reducing wildfire risk in communities vulnerable to wildfire damage or destruction.

A key feature of this guide is a dedicated section on community engagement and partnerships. Building meaningful connections with residents is essential to driving successful community-wide risk reduction efforts. The guide emphasizes that communication strategies can vary. Some are proactive and interactive, while others are more passive or informational. Understanding when and how to use each approach is critical to success. The guide offers actionable advice on:

Facilitating community meetings

Creating effective messaging

Conducting media interviews

Leveraging social media platforms

Tailoring communication to specific audiences

Additionally, it includes a set of talking points for discussing wildfire and mitigating wildfire risk. These can be adapted to reflect your community’s unique demographics, forest conditions, and available resources, helping to make mitigation conversations more relevant and impactful.

An example of talking points from “Fire as Part of the Landscape”

FACNM Leader Spotlight

Regina “Gina” Bonner is the Firewise Committee Chair for Taos Pines Ranch POA, which is in an unincorporated region of SW Colfax County near the Village of Angel Fire. Gina has been a FACNM Leader since the beginning of 2023 and has made numerous significant contributions to building wildfire resiliency within her community. Below highlights some of Gina’s experiences and takeaways since joining the FACNM Network:

Q: Describe a life experience that helped shape your dedication and/or passion for your current work in building fire adapted communities.

A: I’ve always enjoyed the outdoors and natural resources. I’ve hiked and backpacked all over the state, and have catalogued rocks, fossils, birds, trees and wildflowers in Taos Pines Ranch. I will say, though, that the 341,471-acre Hermits Peak / Calf Canyon wildfire south of us definitely motivated me to get more involved in regional wildfire protection over and above Taos Pines Ranch Firewise.

Q: When you think about your work in wildfire preparedness, what is your vision for your community?

A: Reducing the wildfire risk rating for not only Taos Pines Ranch but also surrounding communities through fuels reduction and defensible space projects. This is important because fires do not recognize county or community boundaries. All of The Enchanted Circle has a high wildfire risk rating and should be considered as a whole for landscape treatments, forest health and watershed protection.

Q: What are one or two projects, partnerships, or efforts you’re especially proud of?

A: Partnering with the Cimarron Watershed Alliance (CWA) to write USDA Community Wildfire Defense Grants (CWDG) for SW Colfax County. This was done first as Taos Pines Firewise and later as a CWA board member. Affected communities in the awarded fuels reduction contracts thus far are The Flying Horse Ranch, the unincorporated areas of Moreno Valley and Ute Park, and Angel Fire.

Since CWDG is predicated on having a current Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP), I value partnering with the Forest Stewards Guild to get priority projects and action plans into the Colfax County CWPP.

Q: What challenges or barriers have you faced in your work, and how have you worked through them?

A: Many property owners in Taos Pines are part-time and don’t have a good appreciation of the wildfire dangers because of the precipitation and humidity levels in their other environment. The idea of cutting down any tree, much less for defensible space, was of great concern because they wanted to live in a forest up here and not in the city. The resistance was slowly overcome over time through annual education, having annual chipper days, illustrating fire patterns overlain over Taos Pines lot lines with homes using fire SimTable exercises; plus the preponderance of wildfires near us. We are heading into our third thinning initiative and, once complete, 85% of the 1,200 Taos Pines lots will have been thinned at least once, and some twice.

Q: How has being a part of the FACNM Network supported or shaped your work?

A: FACNM supports Firewise by offering microgrants that can be applied to chipper day and education events. It’s always nice to meet and exchange ideas and lessons learned from other leaders across the network. FACNM website offers a wealth of resources and research on emerging topics like Insurance Institute for Home & Business Safety (IBHS) standards for wildfire prepared homes that are coming to New Mexico.

Q: What advice would you give to someone stepping into a similar role or just beginning this work?

A: Take advantage of the FACNM resources for meetings, workshops and materials. Reach out to them or other peers to explore grant opportunities and to get helpful tools. There is a lot to learn but a lot of resources to help because “you don’t know what you don’t know”.

Resources and Opportunities

Classes and Workshops

IFTDSS Course for Prescribed Fire Plans

online course, Enroll Now

Learn to use IFTDSS, available anytime on the Wildland Fire Learning Portal, for Burn Plans:

Use spatial modeling and include visuals in your plan

Element 4: Describe your Burn Unit with IFTDSS reports and fuel model data from LANDFIRE

Element 7: Build your prescription by using IFTDSS Compare Weather/Fire Behavior

Element 16: Find your critical holding points by running Landscape Fire Behavior

Element 17: Game out spot fires and escape scenarios with Minimum Travel Time (MTT) for your Continengency Plan.

Community Wildfire Protection Plans 2.0 Webinar Series

presented FAC Net and the Watershed Research and Training Center

Session 2: Integrating Smoke Preparedness into CWPPs

Wednesday, June 18 - 11AM to 12:30PM (MT)

Are you planning for smoke preparedness and mitigation in your community and looking to embed that work into your Community Wildfire Protection Plan? Join our discussion and talk with experts about tips and resources for integrating smoke considerations into your CWPPs

Fire-forward media

Weathered: Inside the LA Firestorm (T.V. Episode)

"Weathered" is a PBS series hosted by Maiya May that focuses on natural disasters and extreme weather events. The series explores the impacts of climate change and how communities can prepare for and respond to these challenges. In this episode, the host investigates what caused the 2025 LA Wildfires and how we can prevent future disasters.

Wildfire Wednesdays #145: Post-Fire Effects and Lessons Learned

Happy Wednesday, Fireshed Community!

This year’s wildfire season will soon come to a close across the west, but that doesn’t mean that the impacts of recent wildfires are no longer a concern. As many people in New Mexico know, the fire itself is just the start of a much longer post-fire recovery journey. Today’s Wildfire Wednesday offers some interesting research on post-fire landscape effects and highlights an ongoing educational webinar series which aims to answer some of the most challenging questions related to post-fire recovery and management.

This Wildfire Wednesday features:

Event: Post-Fire webinar series from the Northwest

The Reburn model: how post-fire landscapes react to and burn under future ignitions

Unexpected post-fire effects: fire scars informing weather

Upcoming learning opportunities: 4th Southwest Fire Ecology Conference

Take care and enjoy these last warm days of autumn,

Rachel

Events

Post-fire webinar series from NWFSC and WA-DNR

The Northwest Fire Science Consortium and Washington State Department of Natural Resources are hosting an ongoing informational webinar series on post-wildfire recovery featuring speakers and lessons learned from across the West. All webinars take place on Wednesdays through October/November from 12-1pm PT / 1-2pm MT. Presentations will be recorded, so if you miss any in the series you can watch them at a later date on the NWFSC YouTube channel.

Webinar #1: 10/9: RECORDED

Fire Scars on the Landscape: The Science and Management of Debris Flows

Recently burned areas are at increased risk of flooding and debris flows, or rapidly moving landslides. Learn more about the science behind why debris flows happen, and how managers use that science to mitigate these hazards, even ahead of the fire.

Recording: https://youtu.be/qrhYsTCmTW4?si=s5Ms9kpY958ynhZs

Webinar #2: 10/16: RECORDED

Exploring Diverse Community Pathways to Recovery

After a fire, communities have to work together to organize their recovery effort. Local governments and community groups are on the front lines of figuring out what this looks like in their local contexts. A social scientist and a long-term recovery group leader describe the social and organizational processes through which recovery can happen, and how communities may proactively plan for recovery.

Recording: https://youtu.be/oPRQEA27gKs?si=q39cRByMk_uc_tHx

Webinar #3: 10/23: HAPPENING TODAY

Post-Fire Restoration Infrastructure: Adjusting our Systems to New Patterns of Runoff

We reengineer and rebuild after wildfire through a range of treatments, trying to match our built infrastructure to new, amplified patterns of runoff. A national wildfire practitioner speaks to how leaders and policy makers are increasingly recognizing the need to manage the built environment to accommodate these changes, and an environmental engineer shares a powerful story of transformation in the face of repeated wildfire events.

REGISTER: https://tinyurl.com/PostfireRunoff

Webinar #4: 10/30

The Reforestation Pipeline: Ensuring Equitable Access to Replanting

The science behind reforestation is not new, but in a changing climate, new challenges are rising around what to plant, where to plant, and who has access to planting opportunities. Two nonprofit practitioners review the science of reforestation and how we can develop effective governance systems for implementing planting programs that match the scale of fires and fairly meet the needs of the impacted landowners.

REGISTER: https://tinyurl.com/ReplantingPipeline

Webinar #5: 11/6

Recreating and Relating to the Land After Fire

Wildfires reshape recreation access and experiences over the short and long term. A researcher shares emerging science that is revealing how people return to and perceive wildfire-affected landscapes, and a manager shares how they navigate decisions about supporting recreation in these contexts.

REGISTER: https://tinyurl.com/RecreatingPostfire

The REBURN Model

How post-fire landscapes react to and burn under future ignitions

Historically, past fire effects limited future fire growth and severity. These reburn dynamics from cultural and lightning ignitions were central to the ecology of fire in the West. Over millennia, reburns created heterogenous (ecologically and spatially diverse) patchworks of vegetation and flammable fuels that provided avenues and impediments to both 1. the flow of future fires and 2. feedbacks to future fire event sizes and their severity patterns.

These dynamics have been significantly altered after more than a century of settler colonization, fire exclusion, and past forest management, now compounded by rapid climatic warming. Under climate change, the area impacted by large and severe wildfires will likely increase — with further implications for self-regulating properties as described above. An in-depth understanding of the ecology of reburns and their influence on system-level dynamics is necessary to provide a baseline for understanding current and future landscape fire-vegetation interactions.

Conclusions from two 2023 papers (The REBURN model and System-level feedbacks of active fire regimes in large landscapes) found that long periods of fire exclusion during 20th century suppression efforts were unprecedented for relatively frequent fire landscapes, creating large swaths of uncharacteristic decadent mature forest, particularly at higher elevations. The lack of ‘ecological memory’ normally associated with past fires strongly influences subsequent fire behavior and effects, leading to large patches burning with stand replacing fire, followed by generally abundant post-fire regeneration of fast-growing shrubs or conifers. This abundant vegetation and fire-killed tree snags and logs, all of which are readily available to burn, increases the chances of secondary and tertiary severe reburns, with additional implications on carbon storage, emissions, and smoke impacts to surrounding communities.

The biggest takeaway is that unless active fire management is applied to break up forest continuity, future drying trends across the West and the potential for increased lightning activity suggest that burned areas will continue to reburn at mixed - including high - severity, and fire will play an increasingly important role in this synchronized and compositionally simplified landscape as it recovers. A return of prescribed fire or managed wildfire to previously burned areas will start the process of introducing temporal variation and increasing resilience to future wildfires, whereas complete suppression will predispose the landscape to future large and severe wildfires. This means that much of the landmass which is burned and in some stage of post-fire recovery acts as a fire buffer, making it critical for the rest of the forest to remain forest. Burned and recovering vegetation mosaics provide functional stabilizing feedbacks, a kind of metastability, which limit future fire size and severity, even under extreme weather conditions.

Unexpected Post-Fire Effects

Fire scars inform weather and continue to reshape the landscape

In late 2021, William R. Cotton, Professor Emeritus of Meteorology at Colorado State University sat down with The Conversation, an independent collaboration between editors and academics that provides informed news analysis and commentary to the general public. He provided a think piece based on research by himself and his colleague Elizabeth Page on how large fire scars can impact the frequency and severity of post-fire thunderstorms, accelerating the post-fire impacts on the landscape. Read the full article here.

“Wildfires burn millions of acres of land every year, leaving changed landscapes that are prone to flooding. Less well known is that these already vulnerable regions can also intensify and in some cases initiate thunderstorms. Wildfire burn scars are often left with little vegetation and with a darker [often hydrophobic] soil surface that tends to repel rather than absorb water. These changes in vegetation and soil properties leave the land more susceptible to flooding and erosion, so less rainfall is necessary to produce a devastating flood and debris flow than in an undisturbed environment.”

What is perhaps more interesting is that research has shown that burn scars can affect the microclimate within and above the scar, “initiating or invigorating thunderstorms, raising the risk both of flooding and of lightning that could spark more fires in surrounding areas”. This happens through several mechanisms:

Surface temperatures and heat flux increase significantly over burn scars due to lack of vegetation, reduced soil moisture, and lower surface albedo – essentially how well it reflects sunlight. When burned soil is darker, it absorbs more energy from the sun.

“The temperature difference can drive air currents, causing convection – the motion of warmer air rising and cooler air sinking. When that rising warm air draws in more humid air from surrounding areas, it can produce cumulonimbus clouds and even thunderstorms that can trigger rain and flooding.” This leads to burn scars enhancing both updraft winds and precipitation from storms developing overhead by ~15%.

“[For] how long burn scars will continue to fuel storms depends on how arid the region is, how quickly vegetation recovers, [and how the local climate and climatic patterns are changed by global warming]. Forecasters, emergency responders and people living in and near wildfire burn scars need to be aware that these areas are at risk for potential major flooding and debris flows and invigorated storms with a potential for heavy precipitation”, oftentimes for years or decades after the fire has burned. This is exemplified by the experience of Santa Clara Pueblo with Santa Clara Canyon, an area hard-hit by the Las Conchas Fire which is still experiencing highly destructive floods nearly 15 years post-fire.

4th Southwest Fire Ecology Conference

Register for the opportunity to learn and network this November!

The Southwest Fire Science Consortium, Arizona Wildfire Initiative, and the Association for Fire Ecology are hosting the 4th Southwest Fire Ecology Conference in Santa Fe, New Mexico from November 18-22, 2024. With the conference theme, The Southwest Fire Science Journey: Lessons from the Rearview, New and Unfamiliar Routes, and Promising Horizons, participants and organizers seek to gain a better understanding of the past, present, and future of fire in the Southwest, including the roll of burned landscapes and lessons that can be learned from the post-fire environment and applied to future recovery and protection work. This conference will bring together professionals to share knowledge, exchange ideas, and discuss the latest advancements in fire ecology research and management with a focus on the southwestern United States. Register now for a unique opportunity to connect with fellow professionals and engage in stimulating discussions that will shape the future of fire ecology in this region.

Follow the instructions below to register for the Monday Workshops or Friday Field Trips independently. Workshops cost $25 and are held on Nov 18. Field trips (includes lunch & transportation) cost $75 and are held on Nov 22.

When registering, select “Registration for Workshop or Field Trip Only” and select your choice of workshop or field trip by clicking “Select Ticket Options” from this screen:

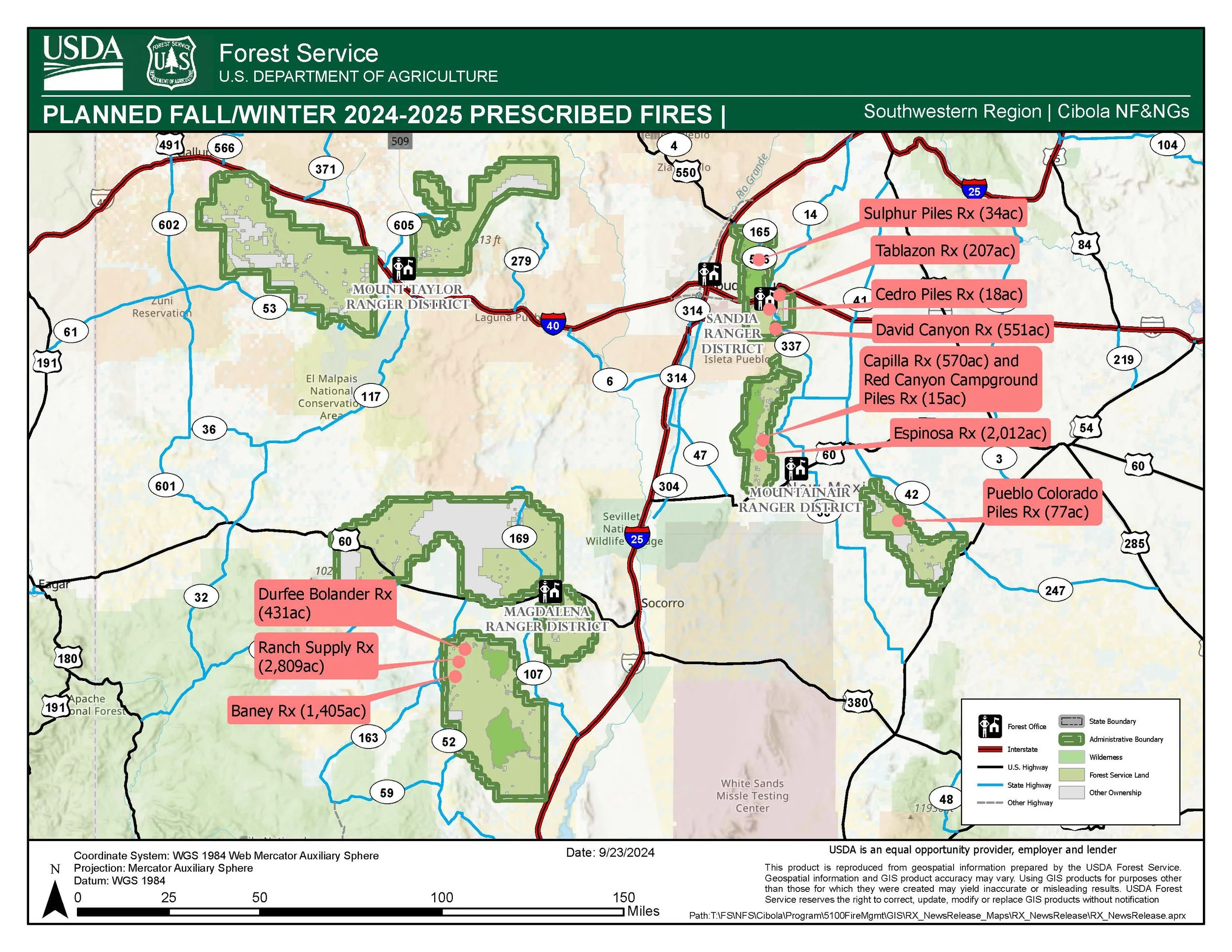

Wildfire Wednesdays #144: Fall Prescribed Fire Season

Hello Fireshed Community,

It’s Fall and there is smoke in the air — and not just from the green chile roasting. Fall is a time when prescribed fires are commonly implemented. With Winter on the way and temperature and humidity dropping steadily, the mild weather conditions of Fall in New Mexico are supportive of the lower intensity prescribed fire that land managers want to see more of on the landscape. Lower intensity prescribed fire allows land managers to accomplish a wide range of ecological and public safety objectives.

Through carefully planning and implementation of prescribed fire, land managers are able to reduce the severity of future wildfires by influencing the residual densities and fuel loadings of forested areas while at the same time supporting nutrient cycling, regeneration, and understory diversity of many fire-adapted forests across New Mexico. The reduction in fire severity that prescribed fire generates not only protects forests from being converted to shrublands by high severity wildfire, but it also supports a more effective fire response from land management agencies, keeping our communities and water resources safer.

So, as you may be smelling smoke in the coming weeks, read on for a better understanding of the rationale and context surrounding the use of prescribed fire on both public and private lands in New Mexico.

This week’s Wildfire Wednesdays, includes:

Prescribed Fire 101

NM RX Fire Council

NM Certified Burner Program

Prescribed Fire Information - NMfireinfo.com

Smoke Exposure Mitigation

NM Wildland Urban Fire Summit - Next week in Taos!

Prescribed Fire 101

Over a century of fire exclusion and suppression has led to negative impacts for fire-adapted ecosystems across New Mexico through the increasing prevalence of uncharacteristically large and severe fires that threaten lives, property, forests, wildlife, and clean water. Wildfires can be reduced in severity and made easier to manage by reducing the density and connectivity of trees within forests and reducing the prevalence of dense forests across landscapes. The pace and scale of forest management needs to increase in order to reduce the threats of large, high severity wildfires, most notably within the wildland-urban interface (WUI) and on private lands.

Both the need to reduce the threat of wildfires by changing fire behavior, and the need to return fire as an ecological process, are addressed through prescribed burning. It is called prescribed burning because land managers carefully prescribe the weather conditions that will support the fire behavior they need to meet their objectives and only ignite the prescribed fire if the current and forecasted conditions match the prescription. Within the WUI, where homes are interspersed throughout naturally vegetated areas, prescribed burning is more difficult and complex. Liability and insurance are two elements that make prescribed burning on private lands difficult, especially within the WUI.

NM RX Fire Council

New Mexico has what is called a Prescribed Fire Council (PFC). These councils are generally statewide organizations that often work in tandem and share many common goals with localized prescribed burn associations. PFCs allow private landowners, fire practitioners, agencies, non-governmental organizations, policymakers, regulators, and others to exchange information related to prescribed fire and promote public understanding of the importance and benefits of fire use.

A map showing which states have Prescribed Fire Councils, from the Coalition of Prescribed Fire Councils, Inc.

PFCs date back to 1975, when the first council in the US was created in Florida in response to rapid development in Miami. Shortly thereafter, the North Florida Prescribed Fire Council was created in 1989 and more explicitly focused on prescribed fire. Neighboring states observed the success of Florida’s programs and began adopting the council model to incorporate federal, state, and private interests. Eventually, prescribed fire councils started to spread beyond the Southeast and across the country. Today, most states have established councils.

For those who want to get involved in New Mexico, membership in the New Mexico Prescribed Fire Council is open to anyone who has a passion for utilizing beneficial fire as a land management tool. Visit the website to become a member or to learn more about the resources provided by the council.

For more information about prescribed fire councils, view this FAC Learning Network webinar recording for a brief overview!

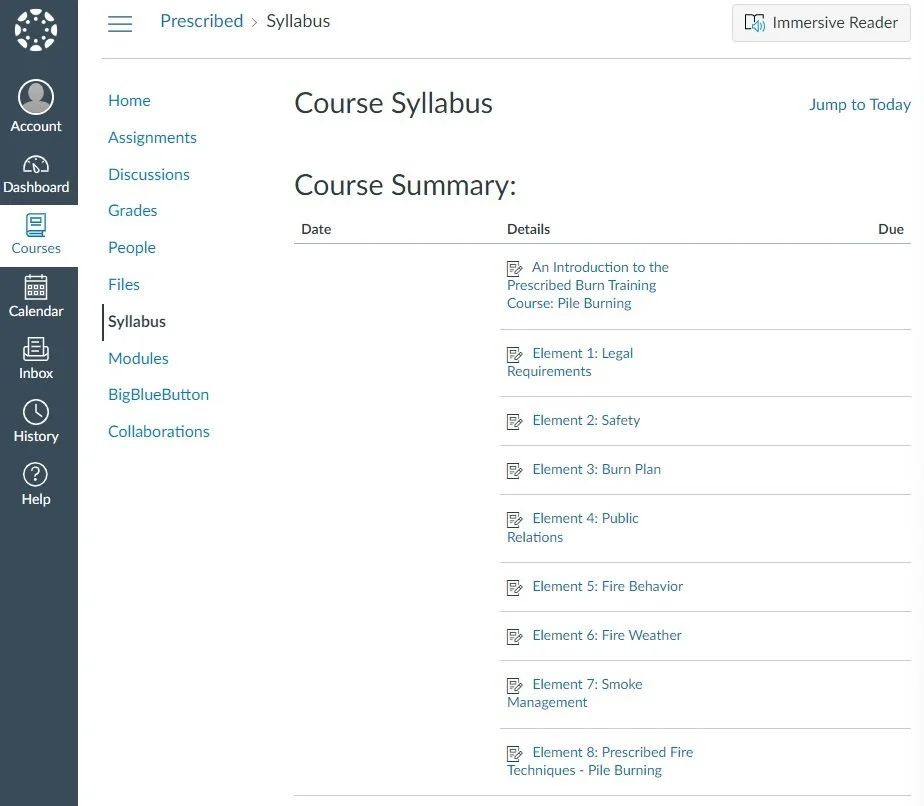

NM Certified Burner Program

New Mexico EMNRD Forestry Division (‘State Forestry’) launched a free publicly available prescribed burning curriculum in autumn 2023. This training, required by the passage of the 2021 Prescribed Burning Act, is accessed through their website. Both primary training and certification waivers are offered through their Canvas portal, where interested individuals can create a free account using the code provided on the Forestry Division - Prescribed Burning webpage. You can choose to sign up for pile burning or broadcast burning courses and progress through the interactive modules which cover topics such as safety, public relations, fire behavior, techniques, etc. Learn more about the Act, and the Curriculum available to landowners and individuals interested in learning how to conduct prescribed burns in a safe manner, by viewing the recording of the FACNM webinar on Supporting Prescribed Fire in New Mexico.

Prescribed Fire Information

NMfireinfo.com

NMfireinfo.com is an interagency effort by federal and state agencies in New Mexico to provide timely, accurate, fire and restriction information for the entire state, including updates about prescribed fires across the state. The agencies that support this site are the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, State of New Mexico, and US Forest Service.

This site is updated as often as new information is available from the Southwest Coordination Center, individual forests, national parks, state lands, tribal lands and BLM offices. The aim of NMfireinfo.com is to provide one website where the best available information and links related to wildfire and restrictions can be accessed.

Smoke Exposure Mitigation

One of the best ways to reduce the impact of smoke is by reducing the amount of smoke that enters your building and filtering harmful particles from the air. If you have a central air conditioning system in your home, set it to re-circulate or close outdoor air intakes to avoid drawing in smoky outdoor air. Upgrading the filter efficiency of the heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning (HVAC) system and changing filters frequently during smoke events greatly improves indoor air quality.

Smaller portable air cleaners are a great way to provide clean air in the areas where you spend most of your time. Essentially these are filters with an attached fan that draws air through the filter and cleans it. These cleaners can help reduce indoor particle levels, provided the specific air cleaner is properly matched to the size of the indoor environment in which it is placed, and doors and windows are kept shut. They should be placed in the bedrooms or living rooms to provide the most effectiveness.

When air quality improves, such as during a wind shift or after a rain, make sure to use natural ventilating to flush out the air in your building.

The Winix 5300-2 and 5500 is what FACNM uses for our HEPA loan program

Selecting a Filter - For either portable filters or HVAC filters make sure to select a filter that is true HEPA or has a MERV rating of 13 or higher. These ratings refer to the size of particles that the filter will remove from the air and in this case they are certified to remove particles down to .3 microns in size. This is the minimum needed to remove the small harmful particles in smoke.

When selecting a portable filter, the other rating to pay attention to is CADR or Clean Air Delivery Rate. This refers to the volume of air that passes trough the unit. A CADR of 200 means the unit provides 200 cubic feet of clean air per minute, and often this number is equated to the room size that it will effectively purify the air in. In a 300 sq foot room a filter with a rating of 200 CADR will cycle the air through the filter 4-5 times per hour. While any filter will provide clean air those with lower CADRs will simply work more slowly. Lastly, make sure to avoid filters that claim to produce ozone to destroy pathogens, as ozone is a respiratory irritant.

More information about filters and guides to selecting one can be found in the Resources section below.

Face Masks - Face masks can be an effective way to reduce your exposure to smoke when they are fit correctly and are the proper rating. Make sure the mask you use is rated at least N95 or N100 and that you take care to fit it properly. These masks will filter out the small particles that are the most hazardous to your health. Paper masks only filter out large particles and will not provide the filtration needed to protect you from smoke.

HEPA Filter Loan Program

With support from the New Mexico State University, the national Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network, and the Forest Stewards Guild, FACNM is pleased to offer this pilot HEPA Filter Loan program. These filters are available to smoke sensitive individuals during periods of smoke impacts in some areas of Northern New Mexico, but we hope to expand to more areas soon. We have a small amount of portable air cleaners that will filter the air in a large room such as a living room or bed room. These will be distributed on a first come- first served basis for predetermined time periods. You will need to provide contact info and come to office listed for your area to sign for the filter and pick it up. Please look over the HEPA Air Filter Check-Out Contract.

To view contact information for the HEPA loan program in your area, visit the FACNM smoke page.

For general information about the program contact Gabe Kohler at the Forest Stewards Guild at gabe@forestguild.org.

Upcoming Events

NM Wildland Urban Fire Summit - Oct. 8-10th in Taos, New Mexico!

October 8th-10th in Taos, NM at the Sagebrush Inn

Join us next week in Taos County for the Wildland Urban Fire Summit! WUFS is New Mexico’s leading event for wildfire preparedness and planning. Join your peers, community leaders, fire service professionals, and federal, state, tribal, and local governments for this in-person event. Community members will share regional history and discuss living in and adapting to the Wildland Urban Interface. Learn the latest techniques, strategies, and resources for wildfire preparedness, mitigation, and recovery. Expand your network of peers and experts to assist you in your fire/disaster resiliency goals. This event is open to the public, and we encourage everyone to attend.

Summit highlights:

Welcome from NM State Forester Laura McCarthy

Property insurance & home mitigation

Taos-region focus & field trip (Wednesday)

Emergency communications

Finding and using funding

Ruidoso 2024 events

Wildfire Wednesdays #143: It Takes a Village to Save a Village

Happy Wednesday and happy autumn, Fireshed Coalition!

As summer comes to a close, western skies continue to be filled with wildfire smoke from blazes in California, Oregon, Idaho, Washington, and other hot and dry forested states. Wildfires continue to follow the trend of igniting earlier and burning later into the year, breaking out of what we have traditionally thought of as ‘wildfire season’ and blurring the lines of property ownership and fire response decision jurisdiction as they race across entire landscapes. What can we do in response to ensure that our homes, businesses, and communities are ready for wildfire year-round?

Emerging guidance from the Institute for Home and Business Safety, United Policyholders, and others suggests that the best protection is strength in numbers. While single parcel defensible space and home hardening has been shown to work, it works a lot better when neighbors meet and do the work together, creating fuel breaks that protect the entire community, designing their defensible space together, and investing in neighborhood-wide protection plans, home hardening upgrades, safety ordinances, and more.

Today’s Wildfire Wednesday features:

Updated guidelines for individual parcel and community level fire preparedness

History and drivers of wildfire

The importance of community-level preparedness

Wildfire preparedness in action: residents and communities returning home after the fire

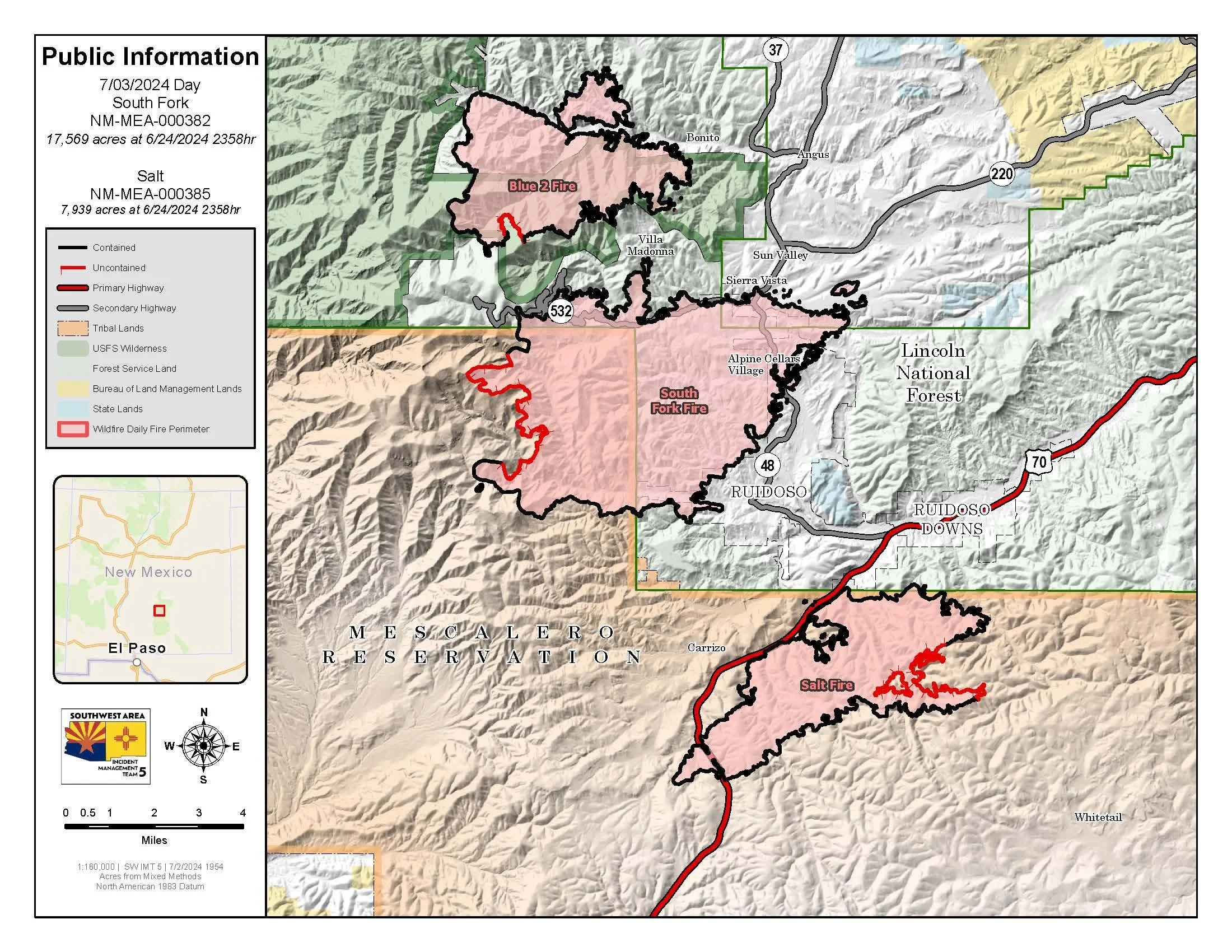

Salt Fork Fire, Village of Ruidoso, NM

Atlas Fire, Circle Oaks, CA

The importance of neighborhood ambassadors

Upcoming events

In the news

Be well and enjoy the equinox,

Rachel

Updated Fire Preparedness Guidelines

Expanding beyond individual parcels to encompass community readiness

The history and drivers of wildfire

For much of the West, fire is part of the natural landscape. However, wildfires become catastrophes when they burn at historically high severity, frequency, are driven by extreme weather, and move into our built environment. This can lead to uncontrollable structure-to-structure fire spread where an urban conflagration unfolds. Urban fire follows humans (population), drought, and wind. New Mexico has these all of these conflagration conditions:

The state has experienced the same population boom as the rest of the West, especially since 2020.

Almost all of New Mexico is in some state of drought and has been since 2019.

The state regularly experiences high wind, which often coincides with and exacerbates dry periods.

Urban firestorms have been a part of cities and their evolution across the globe for centuries. They have been applied as weapons of war as well. The 1666 London Fire was one of the first well documented urban conflagrations. It had similar characteristics to what we see in today’s wildfire-driven built environment conflagrations: drought conditions, human causation for ignition, and a high structure density with fuels between buildings. From the 1600s through the early 1900s, urban fire plagued cities globally (IBHS, The Return of Conflagration in Our Built Environment). Over the last century, we have solved this problem in our city centers but have recreated the risky conditions in our suburban and WUI areas.

The importance of community-level preparedness

The Institute for Business and Home Safety (IBHS) and other prominent fire preparedness organizations recommend using WUI code requirements to increase resilience, in addition to encouraging cities to make different individual, community, and policy choices. In this way, fire science can inform resilient thinking.

Critical elements of fire resilience:

Individual

A non-combustible “zone 0”.

Impenetrable vents and roofs.

Combustible elements between properties - find ways to break those connections.

Community

Parcel-level measures must be implemented at scale (such as fuel buffers along roads) so that communities can break the chain of conflagration and act as fuel breaks, not fuel sources.

Policy

Clustered financial incentives from the State to implement resilient retrofits (treat an entire neighborhood at once).

Require defensible space and fire-resistant design of new homes.

Most buildings are not designed to resist intense flame contact, and once ignited, they contribute as additional fuel to the fire. Therefore, to stall this “domino effect,” maintaining a proper separation between buildings is crucial in a resilient community. High fuel continuity, where fuels are densely distributed and interconnected, can promote the rapid spread of fire, as flames can easily move from one fuel source to another. The concept of fuel connectivity observed in vegetation fuels, such as grass and pine needles, can also be extended to structural fuels such as fences, sheds, accessory dwelling units (ADUs), and other similar objects. The underlying mechanism driving fire spread remains the same: when these structural fuels are closely spaced or connected, heat transfer between burned and unburned occurs at a high rate, leading to rapid fire spread.

It is important to thin, create defensible space, and implement home hardening measuring in and around your own home. It is equally important to talk to your neighbors about their fire risk, and hazards that you share, such as a coyote fence which separates your property but which would act as a connective wick for both homes during a wildfire. It takes action at all levels to prevent a fire becoming a conflagration.

Learn about these and other recommended actions as part of the new Wildfire Prepared Home program from IBHS, a designation program which enables homeowners to take preventative measures for their home and yard to protect against wildfire.

Wildfire Preparedness in Action: success stories from the frontlines

Home hardening, defensible space, and fire ordinances: lessons from the South Fork Fire, NM, 2024

Dick Cooke, Forester for the Village of Ruidoso and FACNM Leader, has been working for a long time to prepare the village for a wildfire. Those preparations were tested when, in June 2024, the South Fork Fire exploded to 15,000 acres in its first 24 hours and rapidly approached the community with ember showers falling a mile in front of the crowning flaming front.

As Dick recounts, when the fire hit the village boundary, it almost immediately dropped from the tree crowns to the ground, creating a more favorable environment for firefighters to work around structures. He credits this to a thinning program that community leaders put in place decades ago. Ruidoso has a fire ordinance that requires all residents and landowners to thin the natural spaces around their homes and businesses to reduce the likelihood of fires spreading, either up or out. In most of the village, the South Fork burned as a ground fire with relatively low flame lengths, allowing firefighters to save numerous homes. However, firefighting personnel still had to contend with extreme weather, a wind-driven flaming front, and the ember storm which preceded the flaming front, with some saying that embers the size of basketballs landed on porches, roofs, and throughout the community.

After evacuation orders were lifted, village leaders started looking around at which houses survived and which burned. They noticed that most of the houses that burned didn’t meet home hardening recommendations. Some had wooden fences that caught on fire and were connected to a wooden deck or some part of the structure that was flammable, causing the fire to spread to the house. There were a lot of homes that use railroad ties in landscaping or as supports under decks, or that had fabric cushions on porch furniture - those ties and cushions caught on fire during the ember storm, which then spread to the house. Even with the ordinance in place requiring residents to thin around their houses, not everyone was following the rules or hadn’t done the work to protect their houses from embers through home hardening. When homes did survive, it’s because they were hardened from embers and flames and the neighborhood vegetation was mitigated (defensible space and forest thinning).

The village is one of the only places in New Mexico with a fire preparation ordinance, so Dick believes that community level preparation made a big difference. 95% of properties in the village have been thinned to get into compliance with the ordinance, with properties being revisited every 10 years to ensure they stay in compliance. The intent of these rules is exactly what Dick saw happen in real time - putting the fire on the ground and preventing it from climbing back into the crown.

Dick believes that the work would have been a lot more effective if the area around the Village of Ruidoso had been treated in a similar fashion. However, the County, which has jurisdiction over the surrounding communities, doesn’t have a similar fire ordinance, and forest treatments on the surrounding National Forest System property were patchy, leading to a mosaic of thinned and unthinned land in the greater Ruidoso area. While each individual subdivision needs to do the work together, they also need to work with surrounding communities to create a cohesive landscape of fire prepared homes, businesses, and wild areas.

Hear about Ruidoso’s efforts from Dick and learn more about safety ordinances, Home Hazard Assessments, and fire preparedness in this archived webinar from Fire Adapted New Mexico.

A neighborhood saved: Circle Oaks, CA, 2017

Cheryl Lynn de Werff was certain her Napa County house was going to burn when she was forced to flee as a massive fire sped toward her Circle Oaks community. It was 1 a.m. and she had just gone to sleep in her second-story bedroom when a sheriff’s deputy pounded on her door. “I came running to the door and he says, ‘Get out! Get out now, there’s a fire coming!’” de Werff recalled. Over the next few days, the Atlas fire burned more than 51,000 acres, killed six people and destroyed more than 300 homes. A week after the community was evacuated, de Werff and her neighbors got the best kind of news possible: all of their homes were safe (Los Angeles Times).

United Policyholders looked into what saved this community when so many others in the surrounding area burned during a rash of intense fires in California’s North Bay in summer of 2017. They concluded that “Circle Oaks in Napa, though evacuated, was largely spared alleged ‘due to vigorous fire prevention programs conducted by residents.’” Several contributing factors aligned to spare the community:

In 2005, a law spurred a change to the Cal. Pub. Res. Code sec. 4291, changing the defensible requirement from 30 to 100 feet. According to CalFire, “proper clearance to 100 feet dramatically increases the chance of your house surviving a wildfire. This defensible space also provides for firefighter safety when protecting homes during a wildland fire.”

The community had spent years installing fire breaks and brush clearance on public land near neighborhoods, which helped to slow the fire.

Neighborhood Ambassadors leading the charge

Firewise Resident Leader! FAC Leader! Spark Plug! Firewise Ambassador! Road Ambassador! Fireshed Ambassador! Neighborhood Ambassador! Volunteer neighborhood leaders who lead wildfire preparedness in their neighborhoods and beyond, regardless of their name or title, can provide great benefits. A wealth of knowledge, skill, tools, and social capacity exists within most neighborhoods, official or not, and working within Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) neighborhoods are a critical scale to improve fire outcomes. Residents in many WUI neighborhoods see firefighters and professional foresters as reliable sources of information; however, these professionals have limited capacity and must focus in high-risk areas where their efforts are likely to yield results. Enter the neighborhood ambassador - because neighbors notice what their neighbors are doing and will often listen to them as sources of information and ideas.

In 2012, the 10,000+ acre Weber Fire blew through a wilderness study area and into the canyon of a neighborhood where wildfire preparedness was being supported through neighborhood ambassadors. The residents’ defensible space and roadside thinning enabled firefighters to protect every structure and build a fire line along their dead-end road and defensible spaces, a feat which would not have been possible a few years earlier. “We ALL had been collectively thinking about THIS fire for a long time. I have told many people that there have been a lot of dedicated folks who have been fighting this fire in their mind, on paper, and on the ground for a decade or more,” wrote Philip Walters, Wildfire Adapted Partnership Neighborhood Ambassador.

Read the full article from 2020 to learn about the origins of the FAC Ambassador Guide, the role that FACNM played in its creation, the importance of neighborhood ambassadors, and real-life examples of neighborhood organization leading to better fire outcomes.

Additional Resources

Upcoming Events

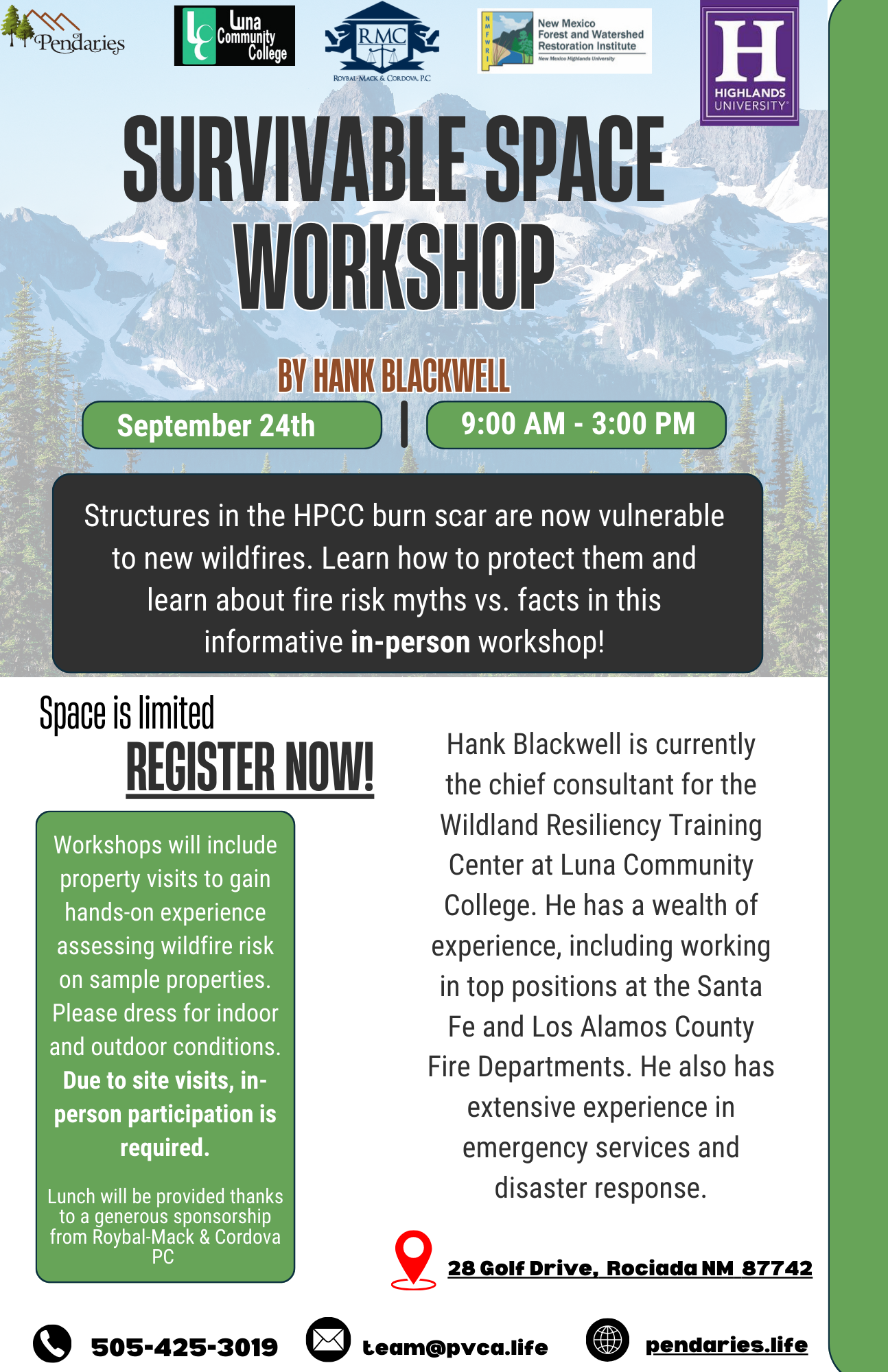

September 24th, 9:00am-3:00pm MT; Rociada, NM: Survivable Space Workshop

It is hard to imagine the possibility of more fires within the HPCC burn scar, but we know it is a reality. What are some simple ways to reduce wildfire risks to homes?

Hank Blackwell, chief consultant for the Wildland Resiliency Training Center, will lead a workshop teaching attendees how to protect structures in the HP/CC burn scar that are now vulnerable to new wildfires. Learn about fire risk myths vs. facts at this in-person event which will include property visits to gain hands-on experience assessing wildfire risk on sample properties.

Space is limited, register now! To learn more, email team@pvca.life or call 505-425-3019.

………………………………….

In the News

Navigating wildfire smoke damage: Insights from the 2021 Marshall Fire

Catrin Edgeley | Northern Arizona University

Dr. Cat Edgeley is a natural resource sociologist interested in social components of forest management. As a wildfire social scientist, she conducts research about how human communities adapt to wildfire. In this presentation she shares research on navigating smoke damage after the Marshall Fire.

………………………………………

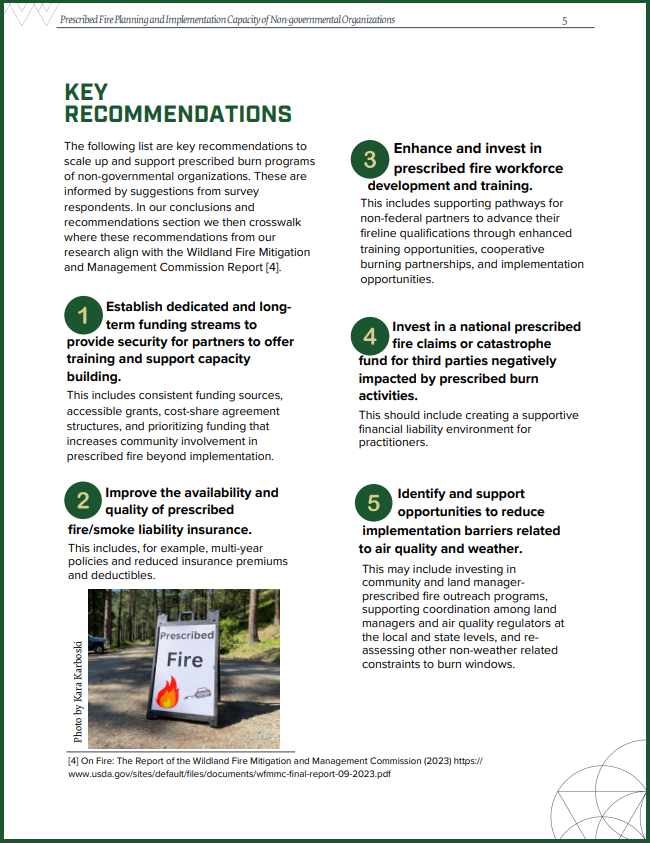

Practitioner Paper: Prescribed Fire Planning and Implementation Capacity of Non-governmental Organizations

In 2022, the U.S. Congress made historic investments in wildfire and fuels management through passage of the Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Researchers from the Public Lands Policy Group at Colorado State University recognized that federal agencies need a better understanding of the community-based capacity available to support and implement prescribed burn projects if they hope to be successful in strategically deploying these funds across ownership boundaries and at scale (i.e., a large enough spatial extent to achieve fuels and fire management objectives). Additionally, there are many unknowns with how the widespread loss or unavailability of prescribed fire insurance policies has affected prescribed fire practitioners and will therefore affect prescribed burn operations in the future.

To answer these questions and inform effective policy solutions for prescribed fire challenges, the PLPC conducted a national online survey for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who plan, support, and conduct prescribed fire. They had four goals in mind when designing and conducting the survey:

Describe the organizations that support, plan, and/or implement prescribed fire in the U.S.

Identify their capacities and resource needs.

Gauge how they may be impacted by the current scarcity of prescribed fire insurance.

Determine how federal resources could be invested to support these organizations’ workforce.

The resulting report finds that NGOs across the West are generally well set up to conduct outreach to landowners, residents, and natural resources practitioners, to administer grants and manage funds, and assist with or lead prescribed fire implementation. There is room for improvement with educational programming, outreach to disadvantaged communities, outreach to Tribal governments, providing trainings and technical support, and improving direct community outreach before and after burns. The report’s key recommendation for scaling and supporting grassroots prescribed fire efforts in the West include:

Establish dedicated and long-term funding streams to provide security for partners to offer training and support capacity building.

Improve the availability and quality of prescribed fire/smoke liability insurance.

Enhance and invest in prescribed fire workforce Invest in a national prescribed fire claims or catastrophe.

Invest in a national prescribed fire claims or catastrophe fund for third parties negatively impacted by prescribed burn activities.

Identify and support opportunities to reduce implementation barriers related to air quality and waether.

Wildfire Wednesdays #142: Diversity of Perspectives in Wildfire Preparedness

Happy Wednesday, Fireshed Community!

Over the past decade, the wildland fire community has been experiencing a paradigm shift from thinking of wildfire resilience in simple terms to recognizing the complexities of risk. An emerging theme within this shift is that simple conceptualizations of risk do not account for the social and ecological diversity of fire-prone areas. From international organizations to grassroots efforts, those groups working to address our wildfire dilemma and work for better fire outcomes are working together to better account for diversity of perspectives and experiences in wildfire preparedness.

Today’s Wildfire Wednesday features:

Recommendations and considerations on diversity in fire adaptation

Vulnerability to Wildfire: Going Beyond Wildfire Hazard Analysis

Better Fire Adaptation: Increasing Efficacy Through Comprehensive Risk Analysis and Collaboration

Living with Fire: the Influence of Local Social Context and Need for Diversity

Be well,

Rachel

Wildland Urban Fire Summit

The 2024 New Mexico Wildland Urban Fire Summit (WUFS) is happening October 8-10 at the Sagebrush Inn in Taos, NM! This is a space for community members, fire service volunteers and professionals, non-profit conservation groups, and federal, state, and local government representatives to gather and discuss challenges, innovations, and solutions for engagement in fire adaptation. During the in-person event, local community members will share regional history and discuss living in and adapting to the Wildland Urban Interface.

This year, the summit will focus on strengthening partnership through diverse perspectives – taking action in the WUI, including how new partners are developed, revitalizing or strengthening existing partnerships, and how the perspectives and resources they can provide help us to take action in our communities.

Agenda highlights include:

Welcome from NM State Forester Laura McCarthy

Property insurance & home mitigation

Taos-region focus & field trip (Wednesday)

Emergency communications

Finding and using funding

Ruidoso 2024 events

Diversity in Fire Adaptation: a Review

Researchers and practitioners from across the management spectrum have begun considering and making recommendations for how to make fire adaptation more diverse and reflective of physical communities, and therefore more effective and innovative, in recent years. Below is a brief collection of challenges, considerations, and recommendations for improving inclusion.

……….……….

Vulnerability to Wildfire: Going Beyond Wildfire Hazard Analysis

Massive wildfires, which are becoming more frequent due to climate change and a long history of fire-suppression, have strikingly unequal effects on minority communities. The Nature Conservancy recently highlighted a study which integrates the physical risk of wildfire with the social and economic resilience of communities to see which areas across the country are most vulnerable, a complexity acknowledged in their resulting “vulnerability index”. The results highlight the difference between wildfire hazard potential and wildfire vulnerability, showing that racial and ethnic minorities face greater vulnerability to wildfires compared with primarily white communities; in particular, Native Americans are six times more likely than other groups to live in areas most prone to wildfires. These findings “help dispel some myths surrounding wildfires — in particular, that avoiding disaster is simply a matter of eliminating fuels and reducing fire hazards or that wildfire risk is constrained to rural, white communities.”

The takeaway is that “ultimately it’s about connections, building relationships and breaking down cultural barriers that will bring us to a better outcome.”

Read the overview and dive into the study here.

……….……….

Incorporating Social Diversity into Wildfire Management

While research suggests that adoption or development of various wildfire management strategies differs across communities, there have been few attempts to design diverse strategies for local populations to better “live with fire.” Building on an existing approach, managers can adapt to social diversity and needs by using characteristic patterns of local social context to generate a range of fire adaptation “pathways” to be applied variably across communities. Each ‘pathway’ would specify a distinct combination of actions, potential policies, and incentives that best reflect the social dynamics, ecological stressors, and accepted institutional functions that people in diverse communities are likely to enact. This inclusion can help develop flexible scenario-based approaches for addressing wildfire adaptation in different situations.

Examples of unique pathway components for advancing fire adaptation through adaptive or collective action include:

Ways to promote property-level residential adaptation

Governance model/structure of collaborative processes

Fuels mitigation focus

Adaptation leadership and relationships

Incident Command teams and outside response

Wildfire impacts/short- or longer-term recovery

Mitigation aid or grants

Resource management focus

Means of communication, message framing

Read more about the pathways approach.

……….……….

More Effective Fire Adaptation Through Comprehensive Risk Analysis and Collaboration

Defining risk

The primary goal of simple risk approaches is to minimize the costs associated with hazards and their management. Simple risk approaches have their roots in actuarial insurance, risk management, and rational choice models.

The primary goal of complex risk approaches is not to minimize or eliminate immediate risk (as in simple risk approaches), but to adapt to the risk over time. Concepts of complex risk stem from scholarship on wicked problems, risk governance, and Second Modernity Risk. The complex risk framework accounts for and expands on simple risk ideas and approaches by explicitly considering the multiplicity of contexts, knowledges, and definitions regarding a particular hazard.

Moving from simple to complex and from exclusionary to inclusive

There is a prevailing tendency of wildfire management agencies and institutions to rely primarily on simple risk approaches to wildfire hazard management that focus on technical risk assessments, such as questions of probability of wildfire event occurrence, but do not reflect the complexity of contemporary wildfire risk. These insufficiently complex conceptualizations of risk do not incorporate and account for the social and ecological diversity of fire-prone areas, reducing options and creativity for addressing risk by disregarding the varied experiences and concerns that influence collective adaptation.

Approaching wildfire as a complex risk can increase adaptation to and coexistence with wildfire by recognizing and accounting for the complexities of wildfire governance amongst a variety of stakeholders who may operate at various scales using different knowledge systems. Such efforts are more likely to yield socially relevant and legitimate strategies for building wildfire adapted communities.

Although centralized simple risk approaches are an often-necessary part of addressing wildfire risk, greater emphasis on wildfire as a complex risk brings attention to the reality that wildfire response and consequences are interconnected - that is, that decisions and outcomes at various temporal points, including mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery, are linked to place-based networks, processes, activities, decisions, and outcomes of other temporal points.

Five principles to increase adaptation to and coexistence with fire through complex risk consideration

Embrace knowledge plurality and purposefully integrate perspectives other than technical expertise.

Including other types of expertise (and thus complexity), especially local definitions of risk and key values of concern, can increase the local relevance and legitimacy of the risk analysis which can be critical to local uptake and implementation.

Use inclusive, accountable, and transparent engagement strategies that incorporate collaborative learning processes.

Effectively implementing the first principle requires participation by a suite of interrelated public and private individuals in an iterative process to find pathways to desirable and feasible situational improvements.

Include underrepresented groups in collaborative processes and wildfire risk governing networks.

By forgoing assumptions that experts fully understand the experiences or abilities of underserved populations ( e.g., Latine, Black, Indigenous and People of Color), more inclusive processes invite more diverse perspectives and, by so doing, can better reflect the differential adaptation abilities of populations and organizations.

Account for potential uneven distributions of risk and resources to address risk.

Existing funding models for natural resource and associated wildfire management efforts tend to favor organizations with resources and capacity to pursue grants or whose views on wildfire risk match predominant policy priorities. As a result, groups or communities who have less access to resources and capacity may find their opportunities unchanged or even diminished, furthering an already uneven distribution.

Re-focus or re-balance investments across spatial, institutional, and temporal scales.

Wildfire investments which are currently concentrated on hazardous fuels reduction, preparedness (hiring and training firefighters), and response (incident management) could be re-focused to provide more resources to a wider range of pre-fire mitigation work and rapid post-fire adaptive recovery for those affected by fire. This means investing in systems of wildfire governance, the social architecture that will support collective action and innovation in ways that are more likely to be responsive to the changing circumstances of on-the-ground fire risk.

Learn more about recognizing complexity, and its inherent diversity, in fire management.

……….……….

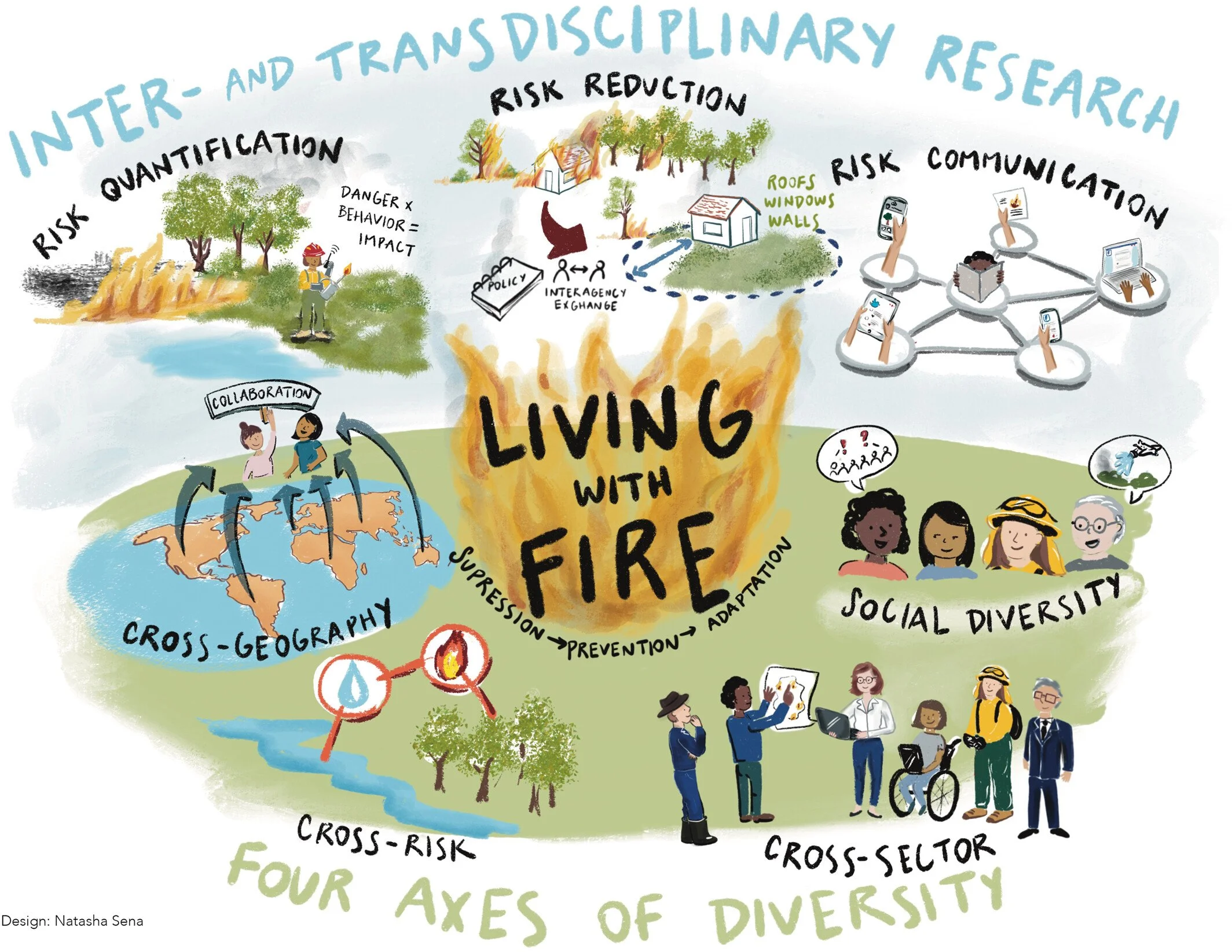

Living with Fire: the Influence of Local Social Context and Need for Diversity

One element of meeting our contemporary wildfire challenge must be accepting fire in the landscape and working with instead of against it; essentially, to change our management paradigm from fire resistance to landscape resilience under the umbrella of Living with Fire. Achieving this integrated fire management approach will require a) understanding the intersecting drivers of fire impacts and risks and b) designing creative and effective risk reduction/management and communication strategies. The integrated fire management model that we are collectively moving toward must include innovation through exchange, adoption, and adaptation.

Living with fire rests on four essential pillars of diversity:

cross-geography (information and knowledge exchange between communities and countries);

cross-risk (learning from water and flood management);

cross-sector (connecting science and practice); and

social diversity (diversity of voices).

With regard to social diversity, there is a growing recognition that human adaptation to wildfire risk is a contingent exercise that may vary across diverse communities. A long history of social science indicates that any effort to improve adaptation is more likely to succeed when it adopts a holistic view of wildfire management that is tailored to emergent patterns of local social context. The unique combination of local history, culture, interpersonal relationships, trust in or collaboration with government entities, and place-based attachments that human populations develop in a given landscape all can have a large bearing on variable efforts to create fire adapted communities. These fundamental differences between and unique characteristics of individual communities can make a big impact on how planning documents (e.g. Community Wildfire Protection Plans), policies (e.g. homeowner risk mitigation requirements), mitigation implementation activities (e.g. home hardening), and education or assistance approaches are written or designed and how, or if, they are adopted by the local community in a meaningful way. Who is at the table and how space is created for everyone to engage matters.

Overall, fire researchers, practitioners, managers, and affiliates must better understand and design diverse strategies for fire adaptation that reflect the social diversity of human communities at risk from wildfire.

In the News

An article in the Santa Fe New Mexican, “Preparation for Wildfires in Santa Fe Starts at Home” recently highlighted the fire department’s community wildfire preparation services - and its wildland-urban interface specialist, Porfirio Chavarria (pnchavarria@santafenm.gov). It focuses on how individual actions tie into landscape-level preparation, saying “fires affect communities, not just individual properties,” and showcases some of the work that Santa Fe has done to improve wildfire outcomes for residents, including community education, wildfire mitigation agreements, home hazard analyses, the fire and weather alert system Alert Santa Fe, and future improvements such as rapid wildfire start detection.

Read more about these services and their success in the article.