Happy Friday, Fireshed folks!

Land managers, fire personnel, private landowners, and others all work, in varying capacities, to care for the land under their jurisdiction. However, caring for the land can mean different things, to different people, in different places. We live in a fire-adapted environment, so fire (prescribed or wildfire) is one consideration when thinking about caring for and managing the land.

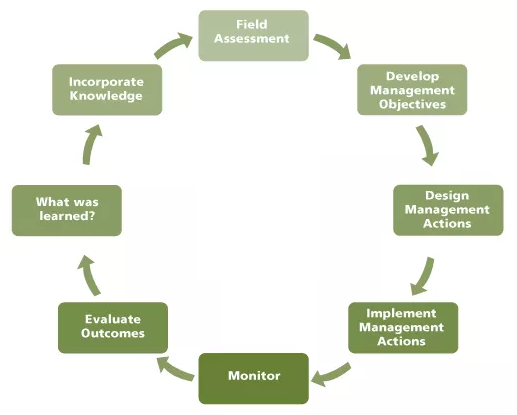

It all begs the question - how do we understand the effects of our land management decisions? How do we improve our management of wildfire, intentional fire, and fire-adapted ecosystems? This is where monitoring (observing and tracking changes in ecosystems over time) and observations-based adaptive management comes in. For fire specifically, we can monitor fire effects (the way that fire changes the area it burns through) to understand the conditions and tools used to influence fire outcomes. Today’s newsletter dives deeper into the what, where, and why of Fire Effects Monitoring.

This Fire Friday features:

Additional resources - webinars, resources, and funding opportunities

Be well,

Rachel

Fire Effects Monitoring: the Basics

What is Fire Effects Monitoring?

Fire effects monitoring is a term used to describe the observation and evaluation of landscape conditions before, during, and after fires. It helps us understand how those fires impact ecosystems, assess management effectiveness, ensure firefighter safety, and guide future land management decisions (a process called adaptive management).

Why is it done?

Safety: observations provide real-time information on fire behavior, spread, perimeter location, and changing conditions that can impact these things for tactical decisions during burns.

Effectiveness: monitoring measures ecosystem health, damage, and benefits over time, providing unbiased data that can be used to evaluate if fires meet hazardous fuel reduction/ecological goals or otherwise improve ecosystem health and function.

Knowledge: knowing real-world fire effects provides actionable data and lessons learned for adaptive management, providing suggestions for improvement on future burns.

Who does it?

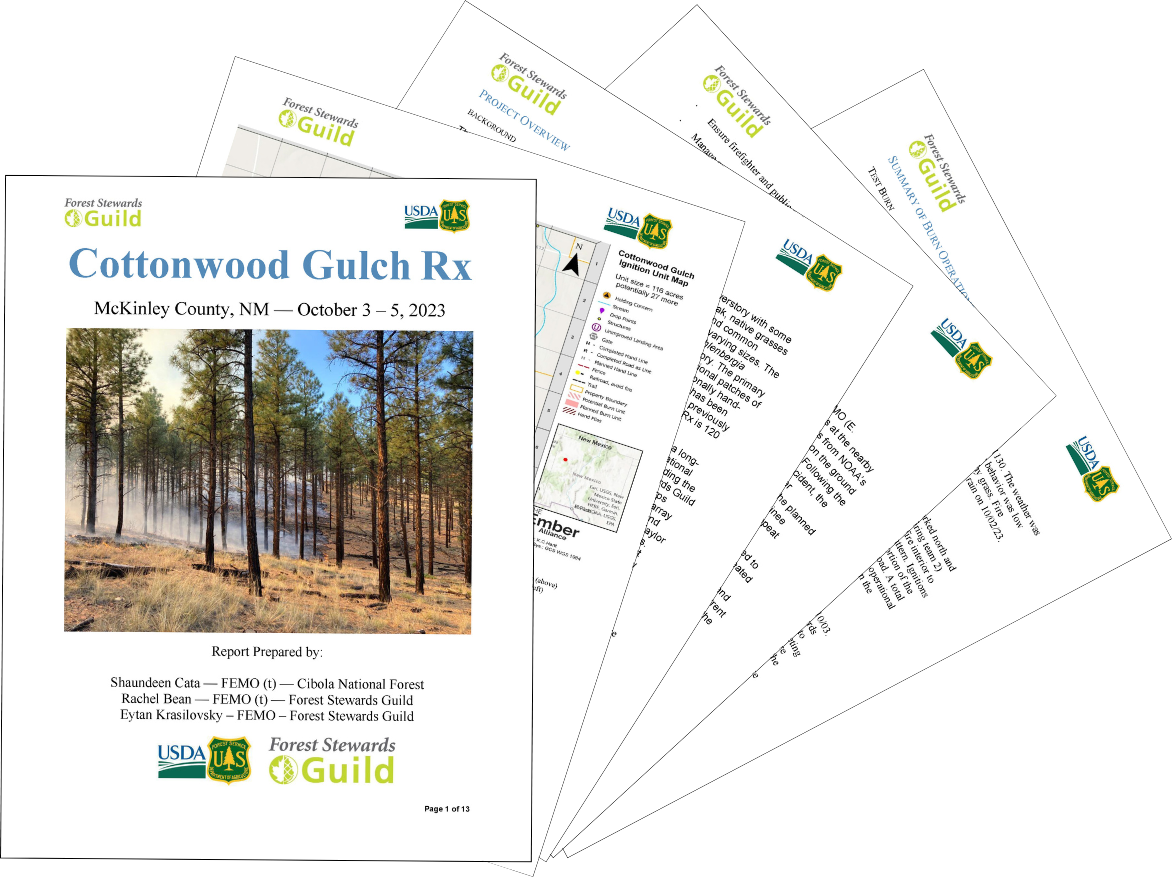

Fire Effects Monitoring Officers (FEMOs), also called Fire Effects Monitors, collect data to inform their team’s understanding of what fire is doing and changing on the ground and help managers assess safety and achieve objectives. They are individuals who have experience with fire and have received training on how to measure and evaluate the different metrics necessary to determine fire effects. Depending on their affiliation, these Monitors will follow different Fire Effects Monitoring protocols and focus on collecting different data. For example, Monitors with the National Park Service regularly and frequently collect in-depth environmental data from specific locations (called plots), allowing them to directly compare pre-fire conditions to post-fire measurements (check out the NPS monitoring handbook for more information). Monitors with the U.S. Forest Service generally focus on providing their personal observations of wildfires to their module leader, crew boss, or other fireline supervisors to inform safety, suppression, and tactical decisions. Monitors with nonprofits, universities, and other organizations will tailor monitoring protocols to their unique needs, or the needs of each individual burn (e.g. focusing on smoke observations during a prescribed burn to ensure that nearby communities are not being unnecessarily impacted).

What is collected?

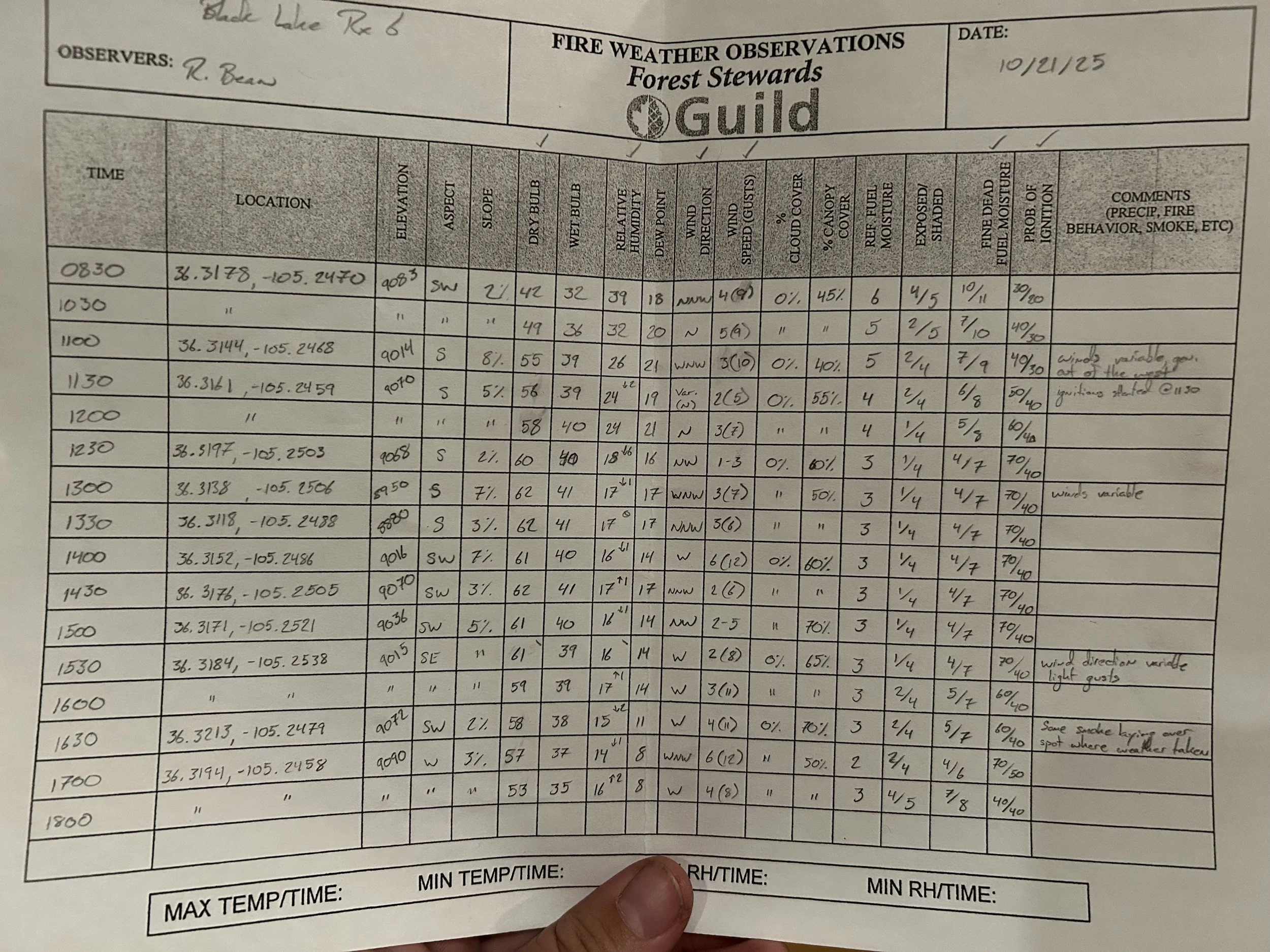

FEMO data collection can include measurements of fuel (amount and condition of flammable material), fire behavior, weather, smoke, and environmental effects on vegetation and fuels. On wildfires, monitoring helps maintain tactical situational awareness for the safety of fire crews and determine whether the team is achieving incident goals. On intentional (prescribed or controlled) burns, monitoring helps to ensure that fire behavior and effects remain within the range of conditions allowed by the prescription (the fire plan which establishes objectives, desired effects, and allowable fire behavior). Some data, like weather observations and fire behavior and spread, will generally be collected daily for each day that the fire is active, while other data, like measurements of fuel and vegetation moisture or amount of fuel consumed, will be collected less frequently. The type and frequency of data collection is based on incident management needs, reporting requirements, and objectives.

How FEMO Findings Are Used

So what happens to all of this monitoring data?

During a burn, a FEMO’s observations may be used to improve the SPOT weather forecast (a location-specific hourly weather forecast from NOAA) or help the burn boss (individual overseeing a prescribed burn) understand whether they are meeting their burn objectives. This can help the whole team adjust their actions and be immediately reactive to improve outcomes in the short-term (while a fire is ongoing).

After a burn, FEMO observations may be summarized into a report which is shared with all incident leaders and partners. FEMO reports provide a clear and fully encompassing written record of a fire’s background, timeline, effects, and lessons learned. They can be referred to after the fact, allowing fire practitioners and managers to see the big picture, learn from their mistakes, and adapt their approach for the next burn, leading to better outcomes in the long term. (e.g. A fire manager might see that fuels reduction objectives were not met because the temperature was low and humidity was high, moderating fire intensity and behavior. From this they could learn that they’ll need to burn that area a little hotter next time to consume the slash and woody debris they want gone.)

FEMO reports can also be shared with external partners and agencies, contributing to collective and collaborative knowledge sharing. As lifelong students of fire there is always something to learn from others’ experiences.

Ecological Benefits of Fire

Periodic, low- to moderate-intensity fire can have many positive effects across ecosystems. Keep reading to learn more or click on any of these resources to dive deeper.

“Cleans” the forest floor

When fire travels through the forest understory, it removes the topmost layer of leaves, needles, and dead or decaying plants. By removing this debris, it opens up space on the forest floor where growth of new plants is encouraged and reduces the amount of fuel that could burn in a future fire, therefore reducing the likelihood of negative future outcomes.

Returns nutrients to soil

The relationship between fire and soil nutrients is complex because of the interactions among many factors. Some soil nutrients will be lost as a low- to moderate-intensity fire consumes organic material in the upper soil layers (greater nutrient losses occurs with higher fire intensity). However, in the long-term fire helps to kickstart the nutrient cycle (the amount of available nutrients in an ecosystem) by increasing soil nutrient turnover rates and redistributing nutrients through the soil profile. For example, soil fertility increases after low-intensity fire as the fire chemically converts nutrients in dead plants that would otherwise take much longer to decay and return to the soil.

Increases diversity

When fire is removed from or suppressed in fire-adapted forests, it leads to over-crowding (trees growing thick and dense) and prevents sunlight from reaching the forest floor, creating intense competition for water and available nutrients. Low- and moderate-intensity fire creates gaps in the canopy, allowing sunlight to filter through and (after several years) increasing the availability of soil nutrients and water. The right kind of fire can also reduce invasive/noxious weed infestations, allowing an opportunity for native plants to grow and establish. Some native species require fire for seed germination!

Creates new habitat

Fire removes thick brush, maintains open meadows, and thins out dense forests, all creating new habitat for animals and birds. Trees that do not survive the fire create new habitat for insects and cavity nesting birds and animals. When a fire burns in a mosaic pattern (burns at variable intensity and severity depending on the terrain and conditions), it creates a diverse patchwork of habitat for different species of wildlife.

Kills pests and diseases

Fire can reduce or eradicate populations of beetles, mites and other harmful pests, reducing disease and keeping forests healthier.

Additional Resources

Upcoming Webinars

27 January, 12pm MT: Aspen Restoration Using Intentional Fire: A Case Study from Monroe Mountain, UT

This webinar from the Southwest Fire Science Consortium and Southern Rockies Fire Science Network will offer information on an aspen restoration case study from south-central Utah which used high-intensity, high-severity prescribed fire coupled with conifer thinning to improve aspen ecosystem health.

4 February, 11:30am MT: Loss of Old-Growth Forest to Fire

Fire suppression and past selective logging of large trees have fundamentally changed frequent-fire-adapted forests. In this Prescribed Fire for Forest Management series webinar, speaker Scott Stephens will discuss the multiple pathways for achieving success in management of mixed conifer forests, with a focus on the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

10 February, 11am MT: Fuel Break Effectiveness: What Have We Learned So Far?

Jen Croft, Stephen Filmore, Mark Finney, Kit O’Connor, Brad Pietruszka and Erin Belval will be the panelists for this webinar in the USDA Forest Service Research & Development Deep Dive Panel Discussions series. This series is intended for fire, fuels and land managers on critical topics associated with fuels and fire management.

12 February, 1pm MT: Policy Update on the Fix Our Forests Act (FOFA)

This policy update presentation from the Forest Stewards Guild and Southwest Fire Science Consortium will provide insights into the Fix Our Forests Act, including the uptake of wildfire management recommendations to congress and the potential impacts on federal land management agencies and the forests they oversee.

…………………………………………………..

Resources

Annual Round Up: Science You Can Use

2025 marked another year of impactful science from the USDA - Rocky Mountain Research Station. Now, all of their bite-sized and information-packed Science You Can Use bulletins, fact sheets, and more from the past year are available in one place, from bees to beavers and biochar to smoke! To listen instead, you can now stream their science.

Click here to view a multi-year archive of science briefs from the RMRS.

Opinion Article from the NM State Forester: Wildfire prevention costs less than suppression

In this article, New Mexico state forester Laura McCarthy calls wildfire prevention “suppression’s undercover partner” and identifies the three fronts for fire prevention: public awareness and early detection, fuel treatments, and individual defensible space and home hardening action. You can learn about the difference between fire prevention and fire suppression in Wildfire Wednesday #107.

…………………………………………………..

Funding

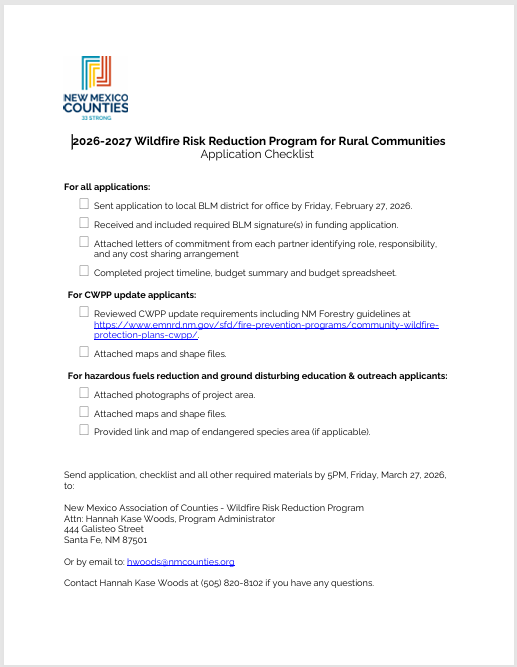

New Mexico Counties is pleased to announce the 2026-2027 Wildfire Risk Reduction Program. The grant program assists communities throughout New Mexico in reducing their risk from wildland fire on non-federal lands. Funding for this program is provided by the National Fire Plan through the Department of the Interior/Bureau of Land Management for communities in the wildland-urban interface and is intended to directly benefit communities that may be impacted by wildland fire initiating from or spreading to BLM public land.

Funding categories include:

CWPP updates up to $30,000/project

Education and outreach activities up to $20,000/project

Hazardous fuels reduction projects up to $100,000/project

The application and checklist are located on the NMC website: https://www.nmcounties.org/services/programs/