Hello, Fireshed Folks!

Fire has always played a dual role in our planet's natural landscapes - an elemental force of destruction and a harbinger of renewal. Yet, within the smoky depths of this paradox lies a method of intentionally engaging with wildfire that has been honed and utilized by traditional communities, natural resources practitioners, fire managers, and others for the better part of a century. This technique has gone by many names but is now commonly known as "managed wildfire." In this week’s Wildfire Wednesday, we explore this practice, tracing its evolution, illuminating its significance, and recognizing the persistent place fire as a tool has and the role it will continue to play in our modern world. This post is based on a recent science synthesis on managed wildfire from the Southwest Fire Science Consortium.

Today’s Wildfire Wednesday features information on:

The concept of “managed wildfire”

How managed wildfire has evolved

Present use and benefits

The intersection of managed wildfire and climate change

Other resources, including microgrant opportunities, webinars, and more

—Alyssa

Defining “Managed Wildfire”

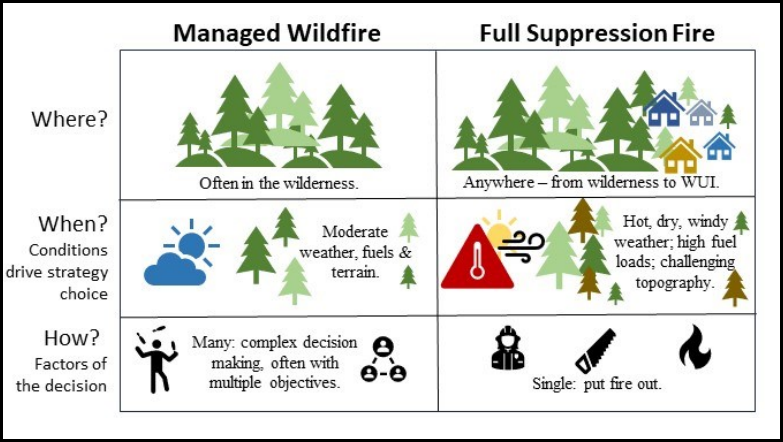

What is the fire response strategy?

"Managed wildfire" is a strategy for responding to naturally ignited wildfires which refers to the deliberate use of wildfire as a land management tool to meet objectives such as firefighter safety, resource benefit, and community protection. This approach recognizes that many ecosystems have evolved with fire as a natural ecological process, essential for maintaining their health and biodiversity. By strategically permitting some wildfires to burn under moderate conditions with close monitoring and layered containment plans, land managers can achieve vital ecological and social safety goals which are otherwise daunting in their scale and need. Similar to prescribed fire, managed wildfires help reduce the buildup of dense underbrush, dead vegetation, and overgrown trees which can otherwise fuel catastrophic blazes. Managed fires introduce diversity, called heterogeneity, to fire-adapted forests. They often burn in a “mosaic” pattern, meaning that some areas will burn at low intensity while others burn a bit hotter with corresponding differences in fire impacts and residual forest density. This fire management technique promotes the regeneration of fire-adapted plant species, enhances habitat diversity for wildlife, and contributes to overall ecosystem resilience.

Embracing managed wildfire as a fire response strategy acknowledges the limitations and dangers of complete fire suppression: some fires which encounter forest conditions shaped by fire exclusion and an absence of land maintenance grow large, destructive, and dangerous to control, posing an elevated risk to firefighters, communities, and the environment. Balancing the art and science of fire management with the proven benefits of fire reintroduction offers a more sustainable and proactive way to mitigate future wildfire risks and live in fire-dependent landscapes.

Read more about wildfires as fuel treatments - burn mosaics and wildfire management.

Historical Use

Fire as an essential ecological process

Indigenous peoples across the globe have long been custodians of the land with practices and knowledge systems that incorporate fire as a fundamental element of land stewardship. In the West, indigenous communities coexisted with wildfire for centuries or millennia before Euro-American colonization. Fire has also been used intentionally to reenergize the land: promoting the growth of edible, medicinal, and materially useful plants; cultivating open landscapes for habitat diversity, grassland browse for wildlife species, and farmer settlements; fire hazard reduction around settled communities; and more.

Suppression as the default

By the 1890s, European settlement resulted in an emphasis on suppression of wildfires. This regard for fire as a destructive force which threatened resources is exemplified by the establishment of the U.S. Forest Service in 1905, whose founding mission was wildfire suppression to safeguard lives, property, and valuable timber. Over the next century, full suppression became the preeminent response to wildfire, albeit with outliers. Technological advances, including the development of fire retardants, improved fire engines, and incorporation of firefighting aircraft, significantly enhanced the ability to actively combat wildfires. This approach, paired with climate change and drought, contributed to ecological imbalances that we are now seeing play out across our forested landscapes.

Unintended consequences of fire suppression:

Ecological Imbalances: over time, wildfire suppression has disrupted natural fire regimes in numerous ecosystems. Fire is an integral part of many landscapes, playing a crucial role in maintaining ecosystem health and diversity. The absence of regular, low- to moderate-intensity fire has led to the accumulation of fuel (called “fuel loading”) and shifts in vegetation composition.

Increased Fire Intensity: these ecological imbalances have contributed to larger and more intense wildfires when they do occur. This intensification can render firefighting efforts more challenging and costly.

Budgetary Constraints: the costs associated with wildfire suppression have soared, straining the Forest Service's budget and diverting resources from other critical programs, including forest management and conservation.

Loss of Fire-Adapted Ecosystems: fire-adapted ecosystems, such as grasslands, savannas, and specific forest types, have shrunk in extent (conversion to other ecotypes) or experienced character change due to fire exclusion.

Fuel loading provides ample resources for future fires to burn hotter, faster, and more intensely. The increased heat and rate of spread generated by such fires can make them difficult to control, posing a significant threat to both the natural environment and human communities. This cycle of fire suppression leading to fuel accumulation leading to catastrophic wildfires can become self-perpetuating. As large wildfires devastate the landscape, the impulse to suppress wildfires becomes stronger. These fires can also create even more favorable conditions for future fires, as dead and downed trees remain primed for future ignition and burned vegetation may not be able to recover as quickly, leaving behind a landscape that is more prone to reburning.

Reintroduction through policy

Federal policies have undergone significant evolution over the years as our understanding of fire ecology and land management practices has deepened. The concept of managed wildfire was introduced and implemented in California in the 1916, but political pushback ended the program after only three years. The National Park Service introduced managed wildfire, then called “natural prescribed fire” or “natural fire management”, to select parks for use the backcountry in the 1960s. A change in wildland fire behavior in the 1990s caused federal agencies to rethink their approach to fire management, and in 1995 the U.S. Forest Service updated their policies to create space for managed wildfire as a response strategy. The federal Departments of Agriculture and the Interior, in 2009, asserted that “fire, as a critical natural process, will be integrated into land and resource management plans and activities on a landscape scale, and across agency boundaries”, and the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) and National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy have since named managed wildfire as a legitimate approach to fire management.

Present Use

Aren’t we “managing” wildfire now?

Technically, yes, all wildfires are managed using a variety of response strategies. As specified by the Chief of the U.S. Forest Service in 2022, “every fire receives a strategic, risk-based response, commensurate with the threats and opportunities, and uses the full spectrum of management actions, that consider fire and fuel conditions, weather, values at risk, and resources available and that is in alignment with the applicable Land and Resource Management Plan.”

The shift in recent decades has been for the Forest Service and other land management agencies to acknowledge the importance of reincorporating fire into land management as an essential and natural ecological process. This is accomplished through prescribed burns and, when conditions are right and a natural ignition occurs in a suitable area, allowing some wildfires to burn without prioritizing full suppression as part of a managed wildfire approach. The goal of reintroduction, regardless of method, is the same: to harness the ecological benefits of fire while mitigating risks to communities, firefighters, and resources. This evolving approach represents a more holistic and sustainable way of responding to wildfires in the face of changing environmental conditions.

A little known but common response

While full suppression is still used as the primary fire response strategy, especially during the hottest and driest months of the year, managed wildfires are a commonplace occurrence on the landscape. The combined footprint of managed wildfires in the western contiguous United States covers an average of 268,000 acres annually, and managed wildfire has been a dominant fire response strategy in Alaska. A strategy other than full suppression is chosen more often later in the season, usually starting after dangerous wildfires have been contained and when managers know that a significant precipitation is likely in the next six to eight weeks. Because managed wildfires generally burn under cool, moist, and moderate weather conditions, they tend to exhibit low- to moderate-fire severity. A managed wildfire strategy is also more likely to be implemented when the fire in question ignites far from communities or other values at risk, is likely to remain small based on natural barriers or containment features, and presents as less complex, requiring the involvement of fewer firefighting agencies and resources. Detailed case studies of managed wildfire found opportunities and obstacles to the strategy were “strongly shaped by local interagency and cross-jurisdictional contexts” such as federal, state, and local policy, Forest Plans, internal agency directives and culture, operational concerns, and real or perceived internal and public support for the strategy.

Benefits of managed fire

Reburns: in general, wildfire has a moderating effect on subsequent fires. Studies have found that in the ten years following a wildfire, subsequent fires experience reduced severity. This is true of managed wildfires, which generally burn under more moderate weather conditions and contribute to variable fire effects and surface fuel reduction that can mitigate future fire risk.

Forest structure: managed wildfires are effective at reducing tree densities, although perhaps not enough to return forests to historic conditions. Even repeat fire entries with predominantly low severity effects are not as effective for bolstering forest resilience as a single managed wildfire with moderate severity effects.

Waterways: in addition to mitigating effects on future wildfires and positive effects on forest structure, bringing fire back to fire-adapted forests benefits streams and rivers, promoting healthy water systems and reducing drought-induced tree mortality.

Cost: when and where wildfires can be managed for resource and community objectives, studies have demonstrated they likely cost less than full suppression wildfires. Additionally, where managed wildfires reduce fuels, they may also reduce the risk and cost of responding to future wildfires that burn through the same area.

Managed wildfires reengage the natural fire regimes that ecosystems evolved with, helping to reduce fuel loading, maintain biodiversity, and reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires. By carefully planning and executing a managed wildfire, land managers can mitigate the long-term consequences of fire suppression policies, contributing to safer and healthier landscapes in the face of a changing climate.

Future Use

Facing the wildfire crisis

Increased management of wildfire for resource objectives will enlarge the area burned each year in the near term but will reduce the number of acres burned at high severity in the long term. Managed wildfire “can improve forest resilience and contribute to restoration efforts in fire-adapted forests,” but potential tradeoffs include increased smoke and declines in certain habitat types. Research comprehensively suggests that any long-term solution to the tremendous wildfire challenge facing communities and land managers across the western US will involve managed wildfire. Managing natural ignitions for resource and community benefit during moderate weather conditions offers hope for limiting future wildfire spread, reducing burn severity, and enhancing suppression effectiveness.

An increase in the frequency and severity of managed wildfires will require careful risk management such as use of emerging fire modeling programs such as the Potential Operational Delineation (PODs) adaptive framework and clear communication with the public. Removing internal barriers, rethinking risk management, and reinvigorating the conversation around reintroduction of fire are logical and necessary next steps to increase utilization and facilitation of a restorative and cost-efficient forest management tool.

Managed fire and climate change

Incorporating the role of managed wildfires into the climate change resiliency conversation is crucial as we grapple with the far-reaching environmental transformations driven by climate change. These shifts encompass temperature variations, alterations in precipitation patterns, and increased frequencies and intensities of extreme weather events. These changes disrupt conventional ecological processes and render ecosystems more vulnerable to disturbances, including wildfires. As a result, understanding the significance of managed wildfires is pivotal in the context of climate change resilience. It underscores the dynamic nature of ecosystems and the necessity for flexible, responsive strategies. Raising public awareness about the ecological benefits of managed wildfires in the context of climate change resilience is equally vital. This can lead to greater support for burn programs and foster a broader understanding of the intricate relationship between fire, ecosystems, and climate change.

Other Resources

Grant opportunity

Fire Adapted Communities NM is offering grants of up to $2,000 to network Leaders and Members seeking financial assistance for:

convening wildfire preparedness events,

enabling on-the-ground community fire risk mitigation work, or

grant proposal development to ensure the sustainable longevity of their Fire Adapted Community endeavor.

Proposals demonstrating community benefit or FAC capacity building are considered on a semi-annual basis; read about project successes funded by Spring 2023 - Round 1 microgrants. Grantees will be reimbursed for applicable expenses up to their awarded grant amount.

Webinars

Wednesday, 13 September at 12:00pm MDT: Grassification and Fast-Evolving Fire Connectivity and Risk in the Sonoran Desert

In the second webinar of a series on invasive grass-driven changes in dry desert systems, presenters will discuss their findings on fire dynamics in the 2020 Sonoran Desert Bighorn Fire near Tucson, AZ to better understand the changing nature of fire in desert systems which are increasingly experiencing conversion to grasslands.

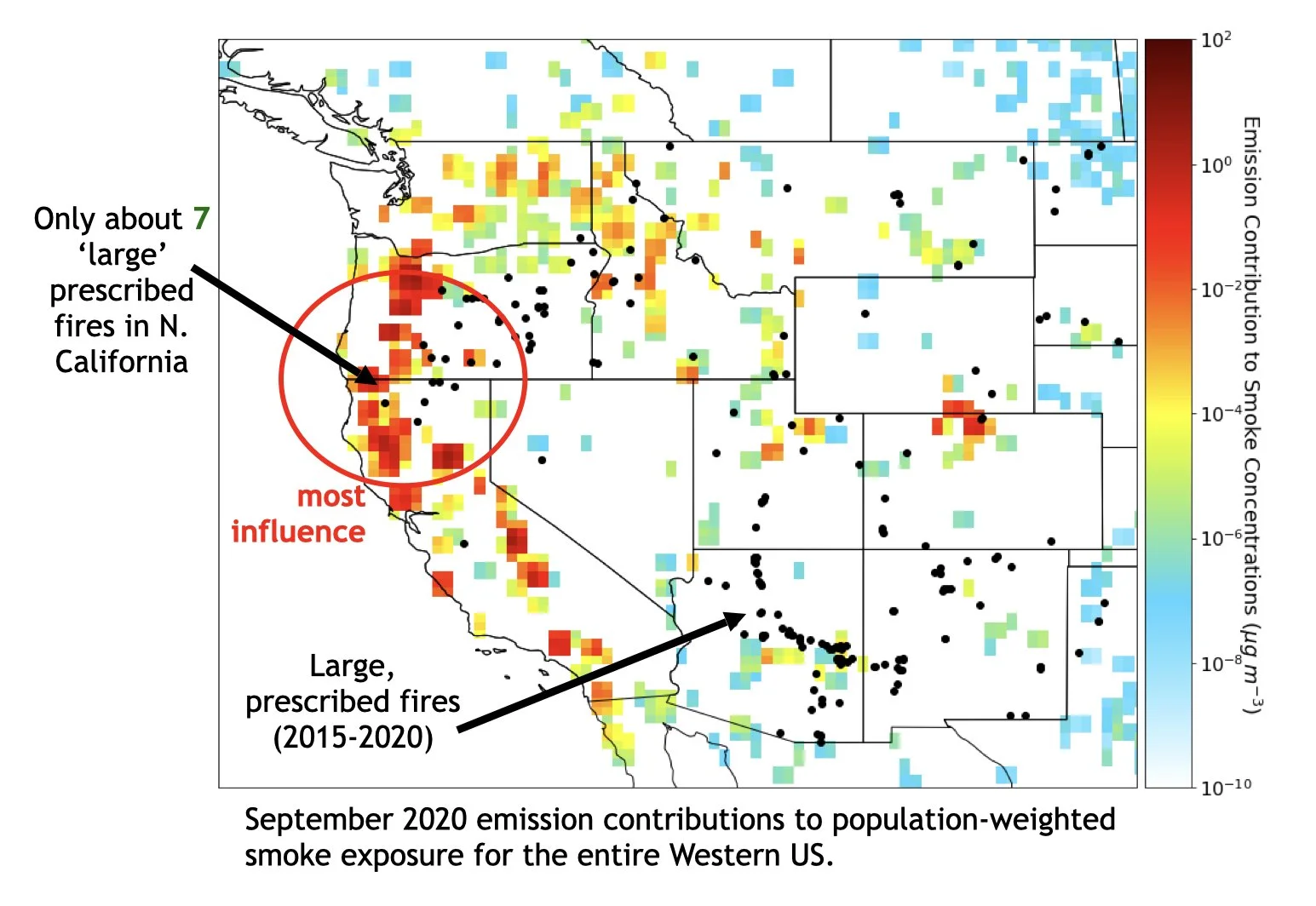

Wednesday, 11 October at 12:00pm MDT: Prescribed Burns as a Tool to Mitigate Future Wildfire Smoke Exposure

Tune in for a webinar co-hosted by FACNM and the SW Fire Science Consortium! This presentation will introduce research on how targeted prescribed burn treatments in heavily forested Western states may have an outsized impact on improving air quality forecasts for the entire western U.S. by reducing the likelihood of future wildfire smoke.

Recent research

Planning for future fire resource needs: the Science You Can Use bulletin titled “Looking to the Past to Plan for Future Wildfire Response” focuses on how characterizing where firefighting personnel and equipment are coming from, both geographically and by managing agency, may help fire managers project how to fill future resource needs.

Giving Power to Communities for Fire Resilience: An Interview from the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network dives into the importance of partnership, meaningful community engagement, and creating local intentional burn opportunities in order to foster community fire resilience.