Happy Wednesday, Fireshed community,

This week is Southwest Wildfire Awareness Week and the theme for this year is “Preparing Together.” After a year that produced the most destructive wildland fires in New Mexico’s history, it’s important to look forward to the upcoming fire season. As families, neighborhoods, communities, and shared partners across the southwest, we resolve to remind ourselves to be conscious of fire, and to help spread that message of awareness. This year, New Mexico is preparing together.

This week’s Wildfire Wednesdays will focus on sharing some legislative updates. Collective action initiatives, like FACNM, have the ability to amplify issues and interests into the policy sphere and effect change from the top-down. While FACNM has not typically delved into the policy sphere, an important starting point for influencing this type of change is to be aware of existing legislation and initiatives that relate to fire and forestry work. With that in mind, this week’s Wildfire Wednesday will focus on sharing updates from our partners at New Mexico State Forestry Division about recently legislation.

Please stay tuned for a webinar this May for a FACNM webinar with New Mexico State Forestry Division where we will share updates on recent legislation.

This week’s Wildfire Wednesday includes a bit of information on the following:

Senate Bill 206 to create a Forestry Division Procurement Exemption

Senate Bill 9 to Create Legacy Permanent Funds

House Bill 195, Forest Conservation Act Amendments

Best,

Gabe

SB 206 - Forest Restoration Procurement Code Exemption

What does SB 206 do?

SB 206 will provide the Forestry Division of the Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department (EMNRD) with a narrow exemption from the state procurement code.

The exemption will be only for contracts that distribute federal grants to non-governmental entities when selected by the U.S. Department of Agriculture or Department of the Interior through the federal agencies’ own competitive application and selection processes.

The Forestry Division serves as the fiscal agency for grant programs established by federal legislation but eligible applicants are not receiving funds because of a conflict with the state procurement code.

SB 206 fixes this problem and makes sure wildfire prevention and forest restoration grants can be distributed to eligible NGOs.

In 2022 alone, more than $250 million of federal funding was available for forest restoration and community wildfire protection projects with NGOs as eligible applicants. More than $1 billion of federal funding for these programs will be available over the next 10 years.

The narrow procurement code exemption in SB 206 will allow the Forestry Division to rely upon the federal agencies’ application and competitive selection processes and enter and administer contracts with NGO subgrantees selected by the federal agencies through those processes.

Without this narrow procurement code exemption, the Forestry Division is unable to contract and administer subgrants for NGO entities the federal agencies have selected through the federal agencies’ own application and selection processes.

The proposed exemption would not reduce transparency or oversight because it is narrow and limited to circumstances where there is a robust federal selection process.

To download the full fact sheet about SB 206 from New Mexico State Forestry Division, click here.

Senate Bill 9 - Creating Legacy Permanent Funds

What is the Land of Enchantment Legacy Fund?

The Land of Enchantment Legacy Fund will be the first state fund solely dedicated to conserving our state’s land and water. Because New Mexico does not have a dedicated state funding stream for land and water conservation, we often have trouble raising federal matching dollars for programs that could better protect communities from wildfire, flood and drought, safeguard our water supplies for urban and rural areas, support our agricultural communities, and grow our outdoor recreation economy.

The Land of Enchantment Legacy Fund will change that, dedicating state funding for existing land and water stewardship programs through a historic investment that will leverage millions of federal dollars and reach all 33 counties and Tribal communities. This will help preserve our cultural heritage and outdoor traditions, leaving a legacy for our children to hunt, fish, farm, ranch, and enjoy the lands and waters the way our ancestors have for generations.

How will it work?

The Fund will not create new programs – instead, it will provide a stable source of funds for programs already administered by six state agencies: the Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department, the Department of Cultural Affairs, the Economic Development Department, the New Mexico Environment Department, the Department of Game & Fish, and the New Mexico Department of Agriculture. These programs have a proven track record of success and are popular in local communities. However, they have never been funded to their full potential. Approving the Land of Enchantment Legacy Fund will boost funding for important programs in the following manner:

EMNRD will receive a 141% overall increase, including a 71% increase for Forest and Watershed Restoration Act programs and consistent funding for Natural Heritage Conservation Act programs for the first time.

NMDA will receive a 331% overall increase, including a 158% increase in Soil & Water Conservation District funding, a 51% increase in funding for the Healthy Soils Program, and consistent stateappropriated funding for the Noxious Weed Management Program.

NMED River Stewardship program will receive an 83% increase.

EDD Outdoor Recreation Division will receive a 450% overall increase, with a 44% increase for the Outdoor Equity Fund and a 470% increase for Special Projects and the Outdoor Infrastructure Fund.

DCA will receive the first consistent state funding for Cultural Properties Protection Act programs.

DGF will receive consistent state appropriations for the Game Protection Fund that will be in addition to receipts from license fees and federal grants.

HB 195 - Forest Conservation Act Amendments

Why do we need the forest conservation act?

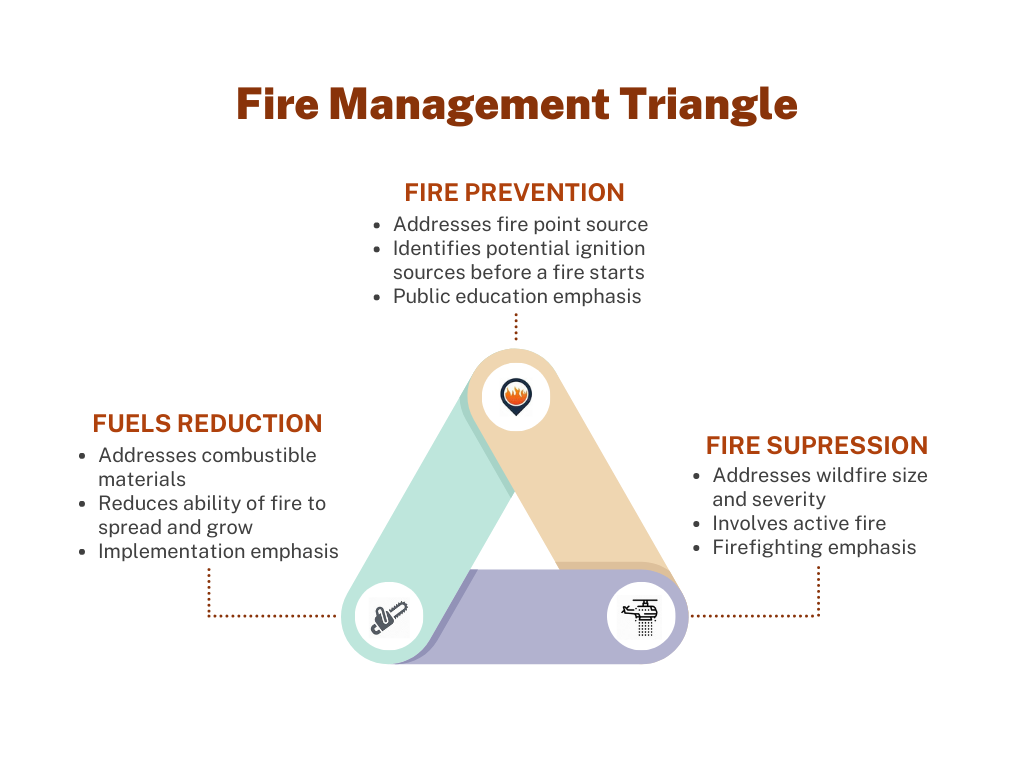

The Forest Conservation Act (FCA), which dates to 1939, is the “organic act” for the Forestry Division within EMNRD. Minor updates to the FCA were made in 1959, 1961, 1967, 1979 and 1987. More than 35 years have passed since the last updates to the FCA, which as currently written is overly focused on commercial forestry and fire suppression.

The 2022 wildfires and post-fire floods provided clear evidence that the needs of New Mexico’s forests are broader than timber production and putting out fires. For example, the FCA does not clearly authorize the Division’s current work on forest health, forest and watershed restoration, or post-fire recovery.

Furthermore, the proposed amendment is also needed to memorialize that the State of New Mexico is authorized to accept federal funding assistance to states under the federal Cooperative Forestry Assistance Act of 1978. The FCA currently cites two federal laws – the Cooperative Forest Management Act and the Forest Pest Control Act – that have been repealed.

What does the HB 195 accomplish?

HB 195 will update the Forest Conservation Act (FCA) to:

cite the correct federal laws that provide federal forestry funding assistance to states;

strike outdated language that conflicts with current state and federal policies;

and strike definitions that are not used. forest fire suppression rehabilitation and repair; post-fire slope stabilization, erosion control, riparian restoration, seeding and reforestation of burned areas; and forest conservation and forest health.

The amendments in HB 195 will also recognize that the Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department (EMNRD), Forestry Division is the contracting agent for the state for:

The amendments will also recognize that the Forestry Division has authority for forest fire suppression and rehabilitation and repair as part of its existing authority to suppress forest fires.

Finally, HB 195 will clarify the grant of authority to the Forestry Division to include conserving forest and forest resources and providing technical assistance to mitigate and adapt to changing climatic conditions.

The amendments will also recognize that the Forestry Division has authority for forest fire suppression and rehabilitation and repair as part of its existing authority to suppress forest fires.

Finally, HB 195 will clarify the grant of authority to the Forestry Division to include conserving forest and forest resources and providing technical assistance to mitigate and adapt to changing climatic conditions.