Glorieta Camps Winter Pile Burning to Continue with Arrival of Snow on January 25th

Glorieta Camps and the Forest Stewards Guild plan to take advantage of favorable weather conditions and continue prescribed pile burning at Glorieta Camps on Sunday, January 25, 2026. This burn will be implemented by the All Hands All Lands Burn Team’s Pile Squad, a program of the Forest Stewards Guild.

Up to 74 acres of piles will be treated with hand ignitions by trained and qualified firefighters working within the parameters of an approved and permitted burn plan. All burn operations will occur with snow on the ground and piles will be patrolled until they are completely out. This prescribed pile burn is a part of a long-term and science-based commitment by Glorieta Camps to improve forest health and reduce the risks wildfire poses to communities, forests, and watersheds.

Smoke and flames may be visible due to the proximity of the site to I-25 and Glorieta. Smoke may be visible from Pecos, La Cueva, and Eldorado. The Forest Stewards Guild works closely with the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) and the New Mexico Department of Health (NMDOH) to monitor air quality during the burn and limit the severity of smoke impacts. This prescribed burn is happening in the context of the Greater Santa Fe Fireshed Coalition landscape. The Fireshed Coalition supports a HEPA Filter Loan Program so that smoke sensitive individuals can borrow a filter for the duration of the impacts.

To find out more and stay up to date, visit: https://facnm.org/our-projects/all-hands-all-lands-burn-team

More information on smoke, human health, and a HEPA Filter Loan Program can be accessed here: http://www.santafefireshed.org/hepa-filter-loan-program

Learn more about Fire Adapted Communities New Mexico Learning Network at www.facnm.org.

An employee of Glorieta Adventure Camps uses a drip torch to light a pile.

Want to learn more?

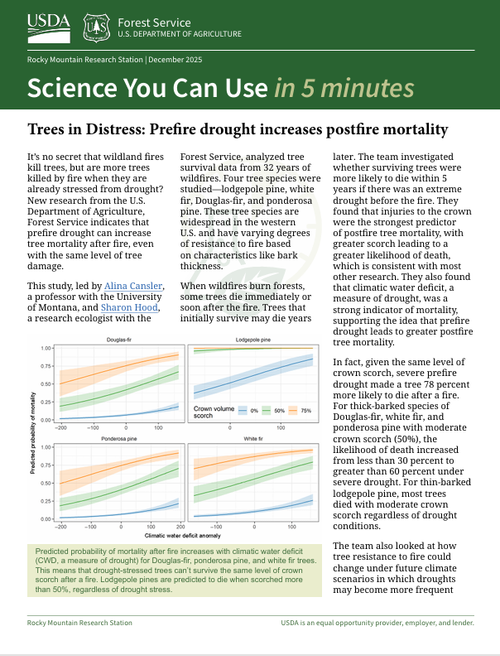

Read the Rocky Mountain Research Station’s “Science You Can Use” booklet on forest treatments (Oct. 2024)

Watch these 4-minute videos from the Nature Conservancy about the importance of:

Forest treatments for water security in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado