Hello Fireshed Community,

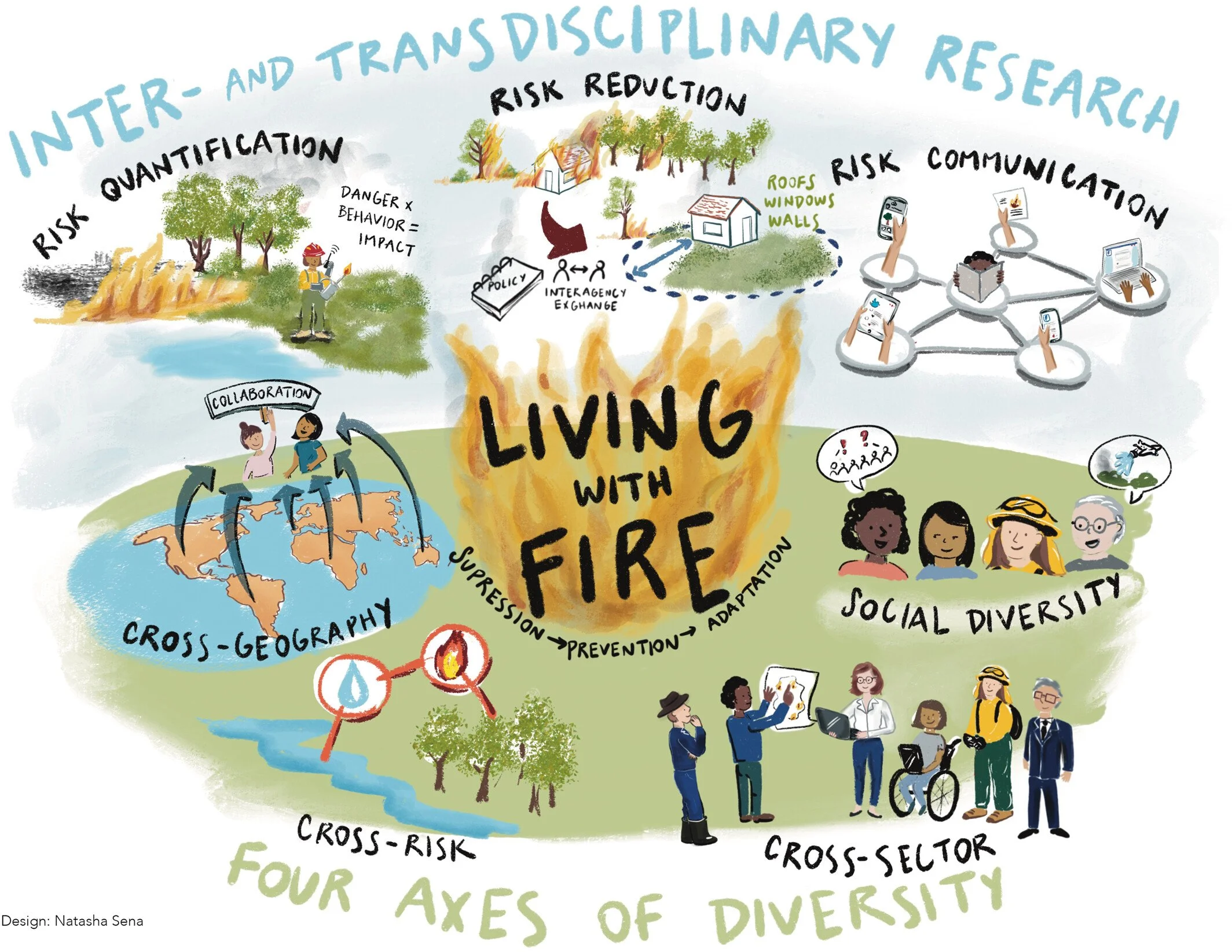

It’s Fall and there is smoke in the air — and not just from the green chile roasting. Fall is a time when prescribed fires are commonly implemented. With Winter on the way and temperature and humidity dropping steadily, the mild weather conditions of Fall in New Mexico are supportive of the lower intensity prescribed fire that land managers want to see more of on the landscape. Lower intensity prescribed fire allows land managers to accomplish a wide range of ecological and public safety objectives.

Through carefully planning and implementation of prescribed fire, land managers are able to reduce the severity of future wildfires by influencing the residual densities and fuel loadings of forested areas while at the same time supporting nutrient cycling, regeneration, and understory diversity of many fire-adapted forests across New Mexico. The reduction in fire severity that prescribed fire generates not only protects forests from being converted to shrublands by high severity wildfire, but it also supports a more effective fire response from land management agencies, keeping our communities and water resources safer.

So, as you may be smelling smoke in the coming weeks, read on for a better understanding of the rationale and context surrounding the use of prescribed fire on both public and private lands in New Mexico.

This week’s Wildfire Wednesdays, includes:

Prescribed Fire 101

NM RX Fire Council

NM Certified Burner Program

Prescribed Fire Information - NMfireinfo.com

Smoke Exposure Mitigation

NM Wildland Urban Fire Summit - Next week in Taos!

Prescribed Fire 101

Over a century of fire exclusion and suppression has led to negative impacts for fire-adapted ecosystems across New Mexico through the increasing prevalence of uncharacteristically large and severe fires that threaten lives, property, forests, wildlife, and clean water. Wildfires can be reduced in severity and made easier to manage by reducing the density and connectivity of trees within forests and reducing the prevalence of dense forests across landscapes. The pace and scale of forest management needs to increase in order to reduce the threats of large, high severity wildfires, most notably within the wildland-urban interface (WUI) and on private lands.

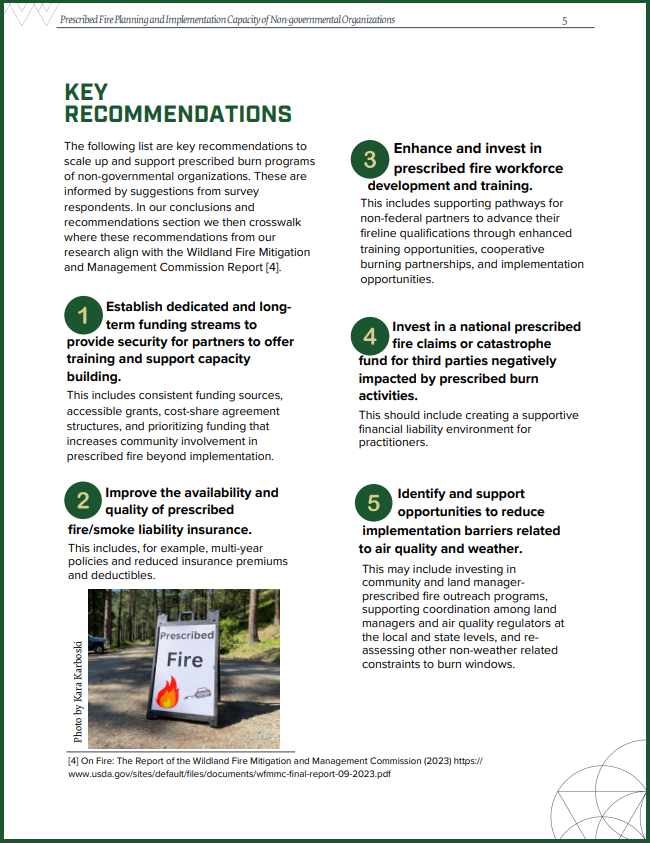

Both the need to reduce the threat of wildfires by changing fire behavior, and the need to return fire as an ecological process, are addressed through prescribed burning. It is called prescribed burning because land managers carefully prescribe the weather conditions that will support the fire behavior they need to meet their objectives and only ignite the prescribed fire if the current and forecasted conditions match the prescription. Within the WUI, where homes are interspersed throughout naturally vegetated areas, prescribed burning is more difficult and complex. Liability and insurance are two elements that make prescribed burning on private lands difficult, especially within the WUI.

NM RX Fire Council

New Mexico has what is called a Prescribed Fire Council (PFC). These councils are generally statewide organizations that often work in tandem and share many common goals with localized prescribed burn associations. PFCs allow private landowners, fire practitioners, agencies, non-governmental organizations, policymakers, regulators, and others to exchange information related to prescribed fire and promote public understanding of the importance and benefits of fire use.

A map showing which states have Prescribed Fire Councils, from the Coalition of Prescribed Fire Councils, Inc.

PFCs date back to 1975, when the first council in the US was created in Florida in response to rapid development in Miami. Shortly thereafter, the North Florida Prescribed Fire Council was created in 1989 and more explicitly focused on prescribed fire. Neighboring states observed the success of Florida’s programs and began adopting the council model to incorporate federal, state, and private interests. Eventually, prescribed fire councils started to spread beyond the Southeast and across the country. Today, most states have established councils.

For those who want to get involved in New Mexico, membership in the New Mexico Prescribed Fire Council is open to anyone who has a passion for utilizing beneficial fire as a land management tool. Visit the website to become a member or to learn more about the resources provided by the council.

For more information about prescribed fire councils, view this FAC Learning Network webinar recording for a brief overview!

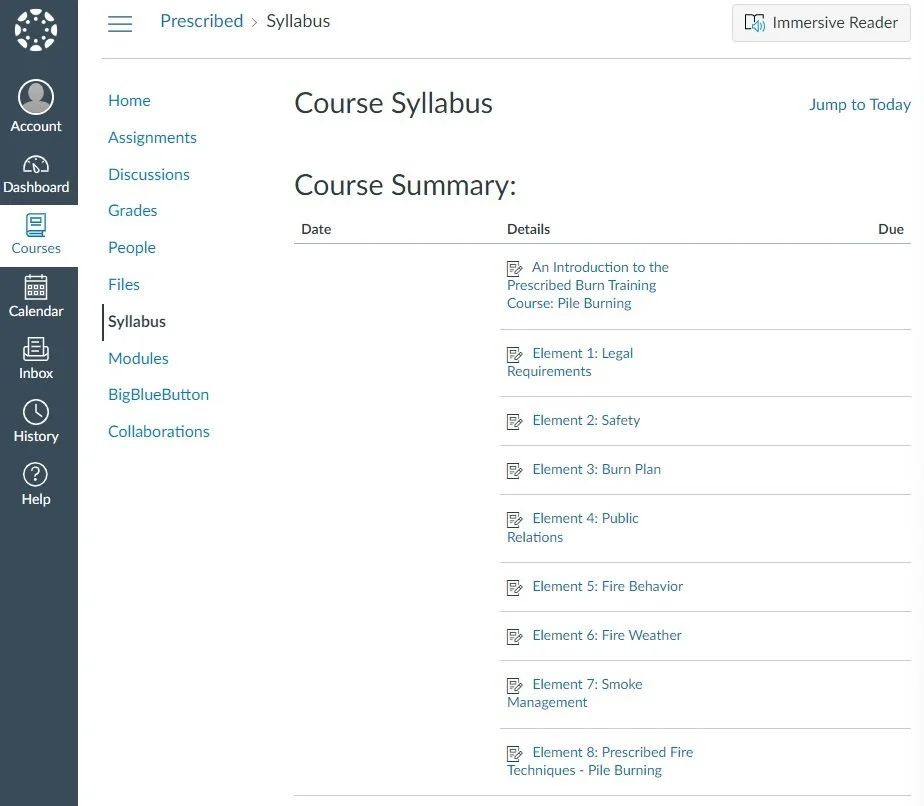

NM Certified Burner Program

New Mexico EMNRD Forestry Division (‘State Forestry’) launched a free publicly available prescribed burning curriculum in autumn 2023. This training, required by the passage of the 2021 Prescribed Burning Act, is accessed through their website. Both primary training and certification waivers are offered through their Canvas portal, where interested individuals can create a free account using the code provided on the Forestry Division - Prescribed Burning webpage. You can choose to sign up for pile burning or broadcast burning courses and progress through the interactive modules which cover topics such as safety, public relations, fire behavior, techniques, etc. Learn more about the Act, and the Curriculum available to landowners and individuals interested in learning how to conduct prescribed burns in a safe manner, by viewing the recording of the FACNM webinar on Supporting Prescribed Fire in New Mexico.

Prescribed Fire Information

NMfireinfo.com

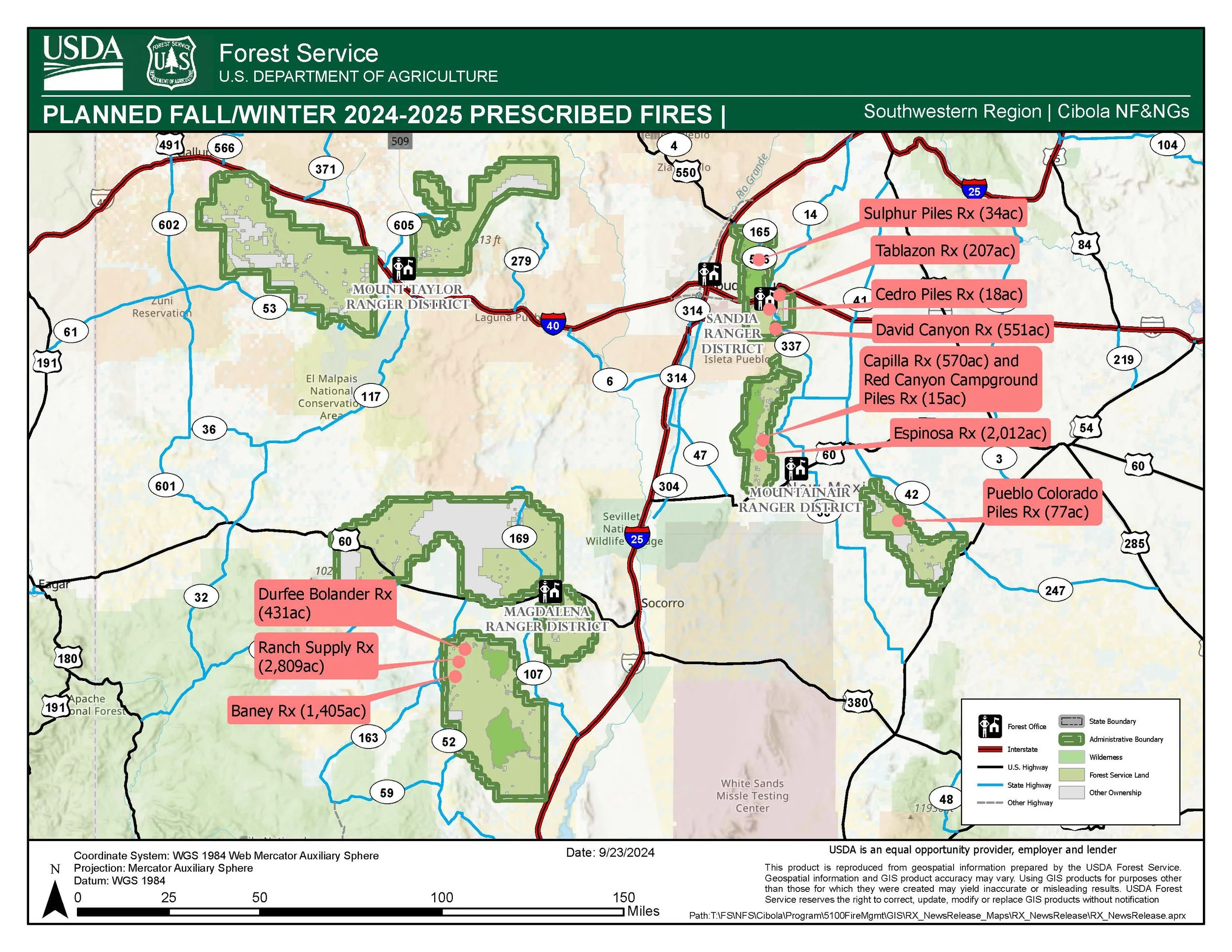

NMfireinfo.com is an interagency effort by federal and state agencies in New Mexico to provide timely, accurate, fire and restriction information for the entire state, including updates about prescribed fires across the state. The agencies that support this site are the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, State of New Mexico, and US Forest Service.

This site is updated as often as new information is available from the Southwest Coordination Center, individual forests, national parks, state lands, tribal lands and BLM offices. The aim of NMfireinfo.com is to provide one website where the best available information and links related to wildfire and restrictions can be accessed.

Smoke Exposure Mitigation

One of the best ways to reduce the impact of smoke is by reducing the amount of smoke that enters your building and filtering harmful particles from the air. If you have a central air conditioning system in your home, set it to re-circulate or close outdoor air intakes to avoid drawing in smoky outdoor air. Upgrading the filter efficiency of the heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning (HVAC) system and changing filters frequently during smoke events greatly improves indoor air quality.

Smaller portable air cleaners are a great way to provide clean air in the areas where you spend most of your time. Essentially these are filters with an attached fan that draws air through the filter and cleans it. These cleaners can help reduce indoor particle levels, provided the specific air cleaner is properly matched to the size of the indoor environment in which it is placed, and doors and windows are kept shut. They should be placed in the bedrooms or living rooms to provide the most effectiveness.

When air quality improves, such as during a wind shift or after a rain, make sure to use natural ventilating to flush out the air in your building.

The Winix 5300-2 and 5500 is what FACNM uses for our HEPA loan program

Selecting a Filter - For either portable filters or HVAC filters make sure to select a filter that is true HEPA or has a MERV rating of 13 or higher. These ratings refer to the size of particles that the filter will remove from the air and in this case they are certified to remove particles down to .3 microns in size. This is the minimum needed to remove the small harmful particles in smoke.

When selecting a portable filter, the other rating to pay attention to is CADR or Clean Air Delivery Rate. This refers to the volume of air that passes trough the unit. A CADR of 200 means the unit provides 200 cubic feet of clean air per minute, and often this number is equated to the room size that it will effectively purify the air in. In a 300 sq foot room a filter with a rating of 200 CADR will cycle the air through the filter 4-5 times per hour. While any filter will provide clean air those with lower CADRs will simply work more slowly. Lastly, make sure to avoid filters that claim to produce ozone to destroy pathogens, as ozone is a respiratory irritant.

More information about filters and guides to selecting one can be found in the Resources section below.

Face Masks - Face masks can be an effective way to reduce your exposure to smoke when they are fit correctly and are the proper rating. Make sure the mask you use is rated at least N95 or N100 and that you take care to fit it properly. These masks will filter out the small particles that are the most hazardous to your health. Paper masks only filter out large particles and will not provide the filtration needed to protect you from smoke.

HEPA Filter Loan Program

With support from the New Mexico State University, the national Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network, and the Forest Stewards Guild, FACNM is pleased to offer this pilot HEPA Filter Loan program. These filters are available to smoke sensitive individuals during periods of smoke impacts in some areas of Northern New Mexico, but we hope to expand to more areas soon. We have a small amount of portable air cleaners that will filter the air in a large room such as a living room or bed room. These will be distributed on a first come- first served basis for predetermined time periods. You will need to provide contact info and come to office listed for your area to sign for the filter and pick it up. Please look over the HEPA Air Filter Check-Out Contract.

To view contact information for the HEPA loan program in your area, visit the FACNM smoke page.

For general information about the program contact Gabe Kohler at the Forest Stewards Guild at gabe@forestguild.org.

Upcoming Events

NM Wildland Urban Fire Summit - Oct. 8-10th in Taos, New Mexico!

October 8th-10th in Taos, NM at the Sagebrush Inn

Join us next week in Taos County for the Wildland Urban Fire Summit! WUFS is New Mexico’s leading event for wildfire preparedness and planning. Join your peers, community leaders, fire service professionals, and federal, state, tribal, and local governments for this in-person event. Community members will share regional history and discuss living in and adapting to the Wildland Urban Interface. Learn the latest techniques, strategies, and resources for wildfire preparedness, mitigation, and recovery. Expand your network of peers and experts to assist you in your fire/disaster resiliency goals. This event is open to the public, and we encourage everyone to attend.

Summit highlights:

Welcome from NM State Forester Laura McCarthy

Property insurance & home mitigation

Taos-region focus & field trip (Wednesday)

Emergency communications

Finding and using funding

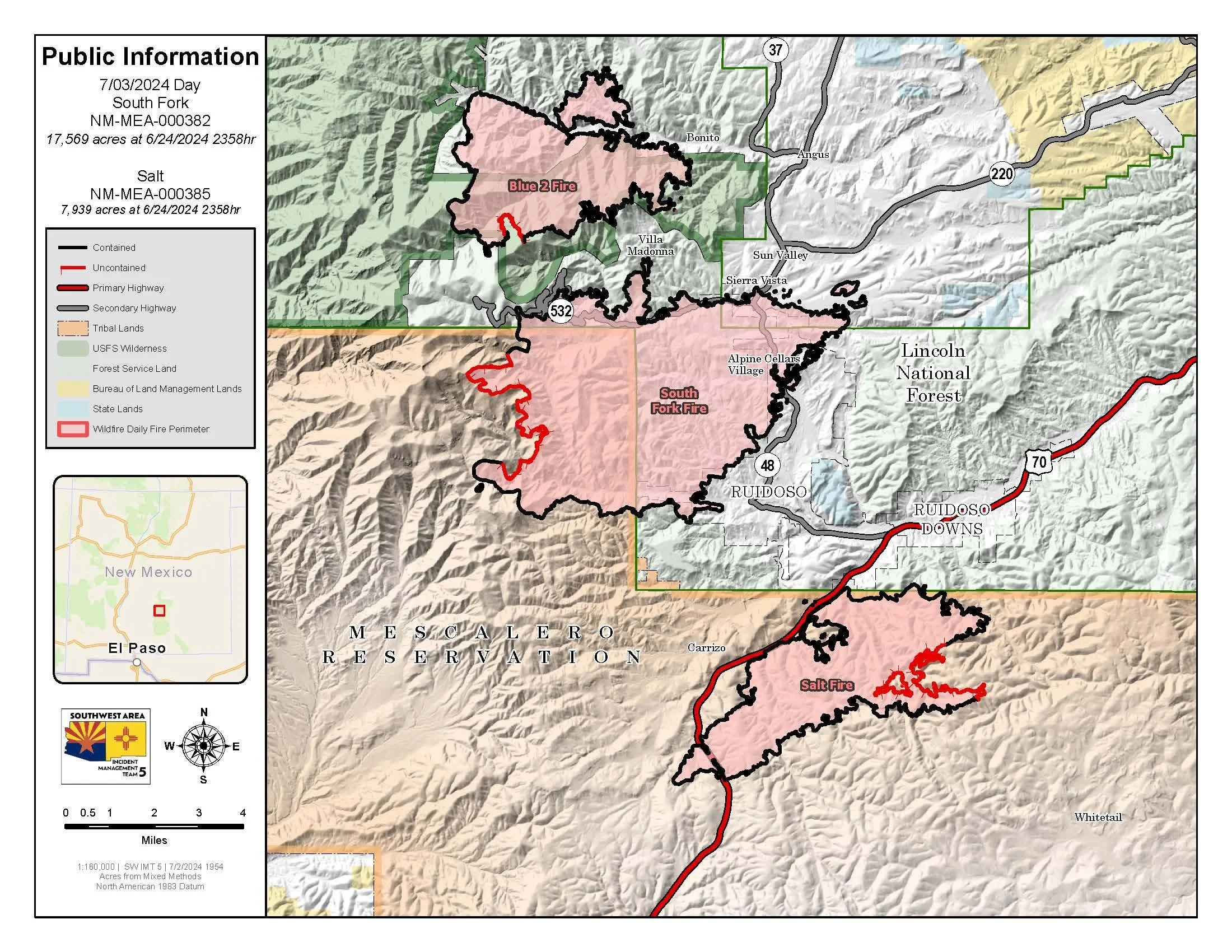

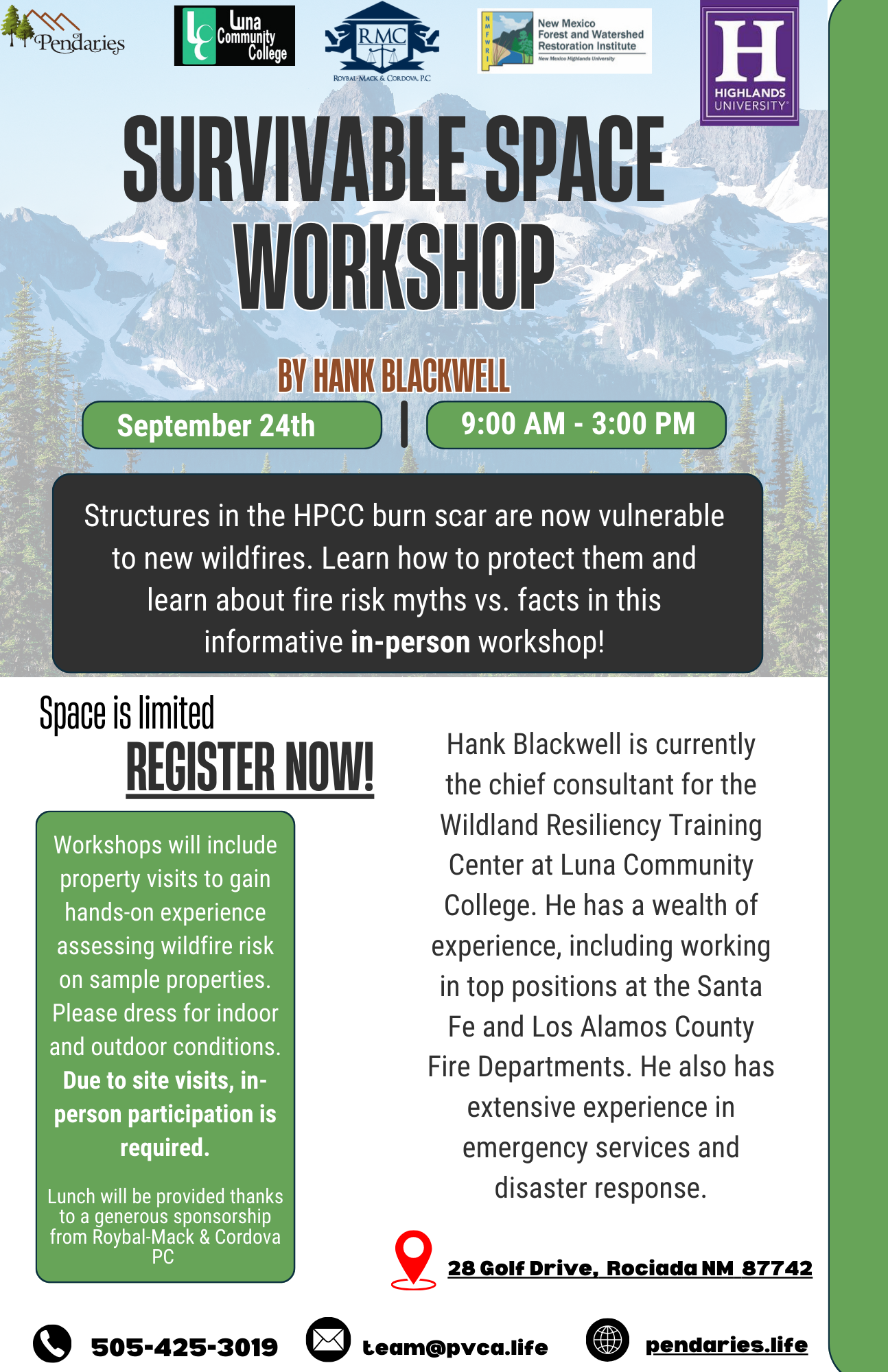

Ruidoso 2024 events